This spectacularly inspiring story of our founding, as dark and complex as it is, has — I think, I hope — the ability to add something to the conversation right now that is unifying.” [1]

Ken Burns

Ken Burns is an American legend. Few documentarians have attracted such attention and acclaim, with his series The Civil War still reverberating in the public consciousness over thirty years after its release.[2] His new series, The American Revolution, examines the story of America’s founding and is particularly timely on the eve of our country’s 250th birthday. The American Revolution is a cornerstone of the United States, and, as Ken Burns indicates in the quote above, it can serve as a unifying force. We can rightfully criticize slaveowners, violent mobs who acted with impunity against loyalists, and the atrocities committed against Native Americans. Even with this taken into account, the core idea of the Declaration of Independence – “all men are created equal” – still holds power today and transcends the flawed individuals we call the Founding Fathers.

Going into America 250, I am trying to read and watch more about the American Revolution and the Founding Fathers.[3] I still consider myself a novice when it comes to this period, but I have read enough that I feel I have more than a passing knowledge of the war. I had very high hopes for The American Revolution; after all, a captivating story in the hands of a master storyteller should be great. What I found, however, is that the series is only good.

Ken Burns has an obvious penchant for military history. While I have not yet seen more than bits and pieces of The Civil War (an admitted shortcoming), it is my understanding it too focuses on the military side of the war. In The American Revolution, the main narrative revolves around the war’s military campaigns, particularly those led by George Washington. Burns makes many of the war’s important battles and campaigns easy to follow, demystifying some of the confusion that minutely detailed looks at troop movements can cause. Burns does a very good job in this series in looking at the broad strokes of a battle’s events, rather than its exacting details.

From the very first episode, it becomes apparent that Native Americans will play a central role in the story. Traditional narratives of the Revolution often do not contain individuals like Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) or General George Rogers Clark, who savagely attacked Native Americans in the northwest. Burns also incorporates the story of the Native Americans who served in the Continental Army, an aspect of the Revolution that I was admittedly unfamiliar with.

In a comparable way, Burns incorporates the stories of women, African Americans, and immigrants into the story of the Revolution. The film shows how multicultural both sides of the American Revolution could be, and how war impacted the homefront. Loyalists, too, play a central role in the narrative, and the idea that the Revolution was essentially a Civil War shines through.[4] This adds nuance and diversity to the story of the Revolution. It is not Americans fighting the British; it is white Americans, Native Americans, African Americans, French, Spanish, Germans, Polish, Swedes, and more fighting the British, Native Americans, African Americans, Hessians, and, crucially, other white Americans.

Economics plays a key role in Burns’ narrative. He shows that colonists’ concerns at the start of the war were not about abstract political ideas but about concrete issues such as taxation, westward expansion, and smuggling. As the war continues, economic issues remain central to the narrative. The economy sways people to be Loyalists or Patriots, leads to the rise of essential financiers of the war, and is cited as a major reason the founders wanted a strong central government.

In short, Burns’ story shows a diverse war with economic origins. It is also a bloody picture that Burns paints, with atrocities on both sides and few clear-cut “good guys” and “bad guys.” The viewer is still left rooting for the Americans in the end. Maybe this is because we know who prevails in the end, or because while both sides acted terribly at times, the Americans still seem to have the ideological upper hand.

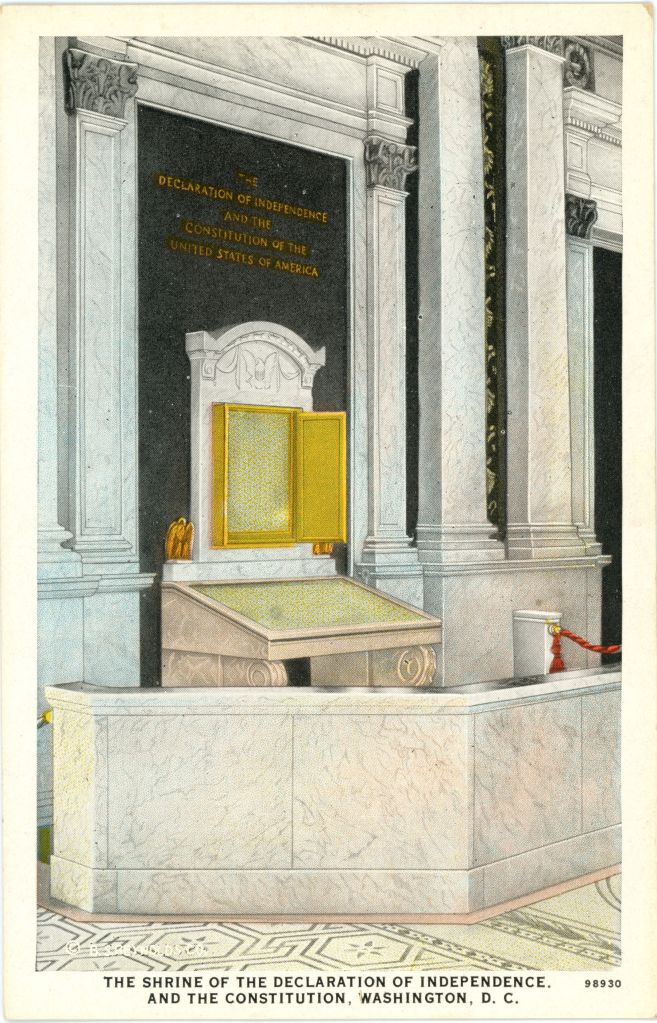

As much as The American Revolution should be admired for its diverse approach to the war, I still found issues with the way the revolution is covered. For one, as good as Burns is at covering the military, it is ultimately a film about the war. The American Revolution is not just a revolution in the military sense, but also in the ideological sense. At the start of the first episode and at the conclusion of the finale, Burns elaborates on the ideas of liberty and freedom we inherit from the Revolution, but it is not a throughline of the story. It is hard to grasp from the film that a group of colonists, concerned about economic problems, would band together to revolutionize political thought. Granted, there are segments devoted to the Declaration of Independence and Paine’s Common Sense, but it is hard to discern how the average American views these political changes. We hear from citizens and soldiers, rich and poor, men and women, white, Black, and Native American voices about the homefront, the war, and life during the Revolution. But how did their thinking about politics, government, and what it means to be an American evolve during these years of conflict? The question remains unanswered.

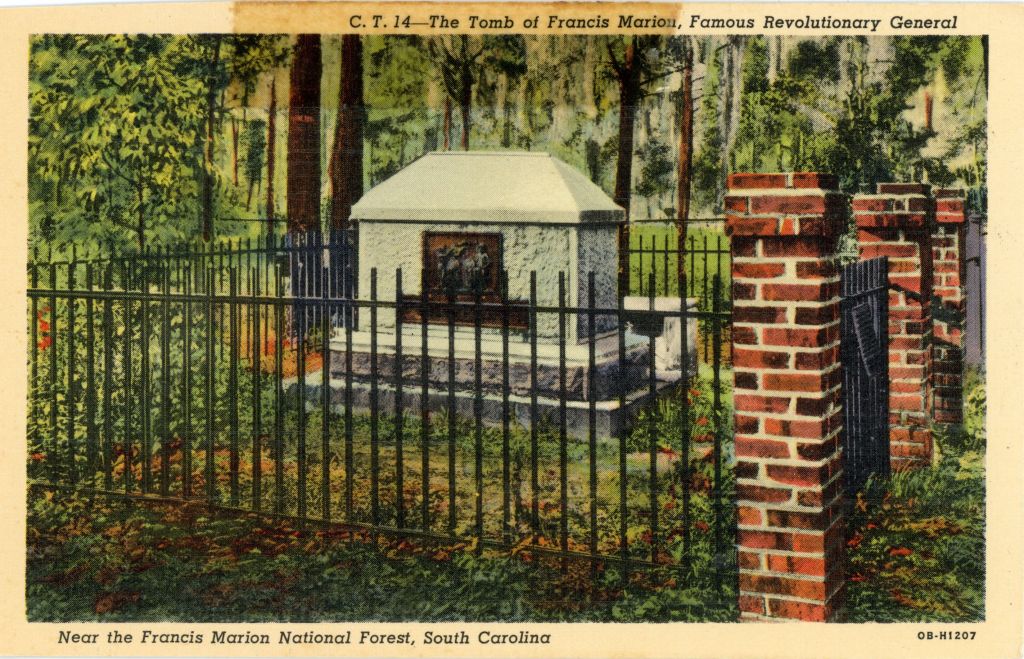

I am naturally interested in the war in the South. My ancestors from the Revolution served in the Carolinas. I grew up learning about the Swamp Fox when passing Francis Marion University on the way to Myrtle Beach, and the Revolutionary War battlefields I have visited are places like Savannah, Cowpens, Kings Mountain, and Charleston. Moreover, I am studying Georgia history, so much of my reading about the war has been focused on the South.[5]

In watching the first four episodes, I was disappointed by how little the Southern Theater of the war was included. In episode five, the sieges of Savannah are covered briefly, and the fighting in the Carolinas becomes important in episode six. Essentially, the Georgia and the Carolinas are covered from the very end of 1778 into 1781. While these years do see some of the South’s most important battles, the South was involved in the war from the very beginning. This series does a very good job of including Loyalists, African Americans, and Native Americans, but few of the voices and stories included are from south of Virginia. Including their perspectives would have made a more well-rounded look at the war.

Burns deliberately focused on only the details of the war that can be substantiated with evidence, which is a very worthy goal. Take, for instance, this quote from a recent interview with Smithsonian Magazine:

One way is to think about it as an absence. Nobody in the film says, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” The name Betsy Ross is not mentioned. We’re not confident enough about Nathan Hale’s final words to say, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” We know that a British officer remarked that [Hale had] gone to his death with “great composure.” There’s no chopping down a cherry tree or throwing a coin across the Potomac. [6]

Ken Burns

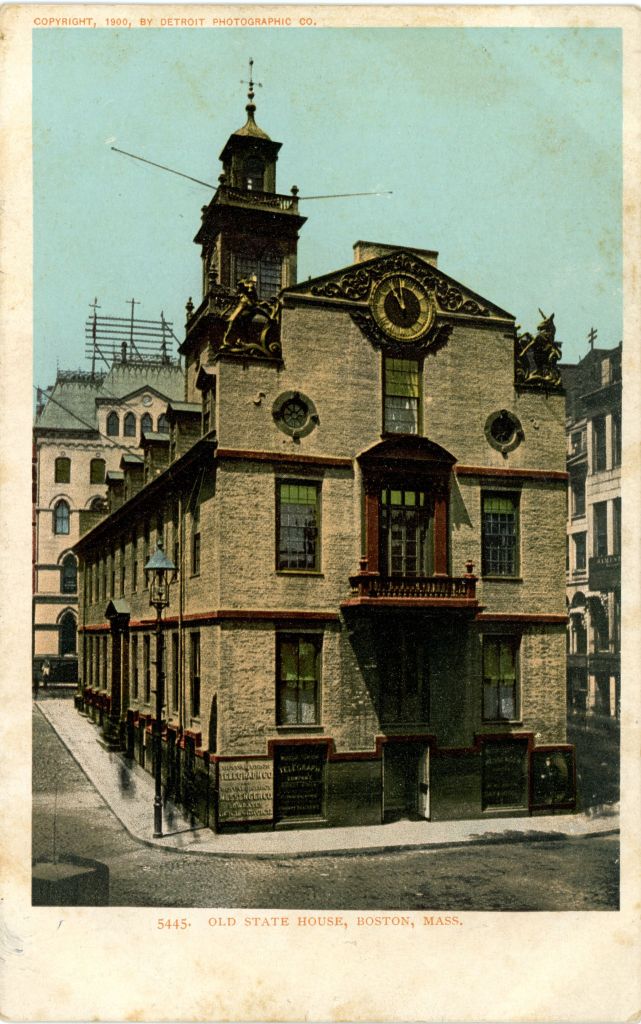

The Revolution is history, but also in many ways mythology. Even if these mythical characters – Paul Revere, Nathan Hale, Nancy Hart, the Swamp Fox, Betsy Ross, Molly Pitcher, William Jasper, and John Newton – are not the heroes they have been made out to be, they have been a crucial part of America’s origin story since the Nineteenth Century. However, there is a reason we tell these stories even if they are exaggerated.

I have no issue with saying something along the lines of “According to legend, Nathan Hale’s final words were ‘I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.’ While these words may not actually originate with Hale, they would become an important part of the Revolution’s story.” We remember these words because they cast the Revolution in a noble light. There may have been violence and bloodshed, but it gave us sentiments we can aspire to today.

These figures were mostly average Americans, but they managed to become a part of the national pantheon. They remind us that we, too, can do great things, and that anyone can shape America’s destiny.

What Ken Burns does well is share a more diverse story of the American Revolution. Through his extensive use of eyewitness accounts from a variety of sources, almost anyone watching can find someone they identify with. It humanizes the war and makes its effects on soldiers and civilians all the more impactful.

What The American Revolution misses is what Ken Burns set out to do: “to add something to the conversation right now that is unifying.” As Americans, we should be able to look at the American Revolution and see the violence and destruction and be moved, even horrified at times. We can look at these diverse individuals and see ourselves. This is accomplished well.

But more than the battles and campaigns of the Revolution, what matters is its legacy. The ideological shift it represents, and the values it gave us, are crucial. The legends of the Revolution are touchstones for our national origin story, and the stories we share about these figures create an element of national mythology. We can recognize these stories’ dubious nature while still acknowledging their importance in the American psyche. The ideology and myth of the Revolution give the period symbolic power that transcends differences. Without this soul, the American Revolution fails to inspire.

[1]. Jennifer Schuessler, “Can Ken Burns Win the American Revolution?,” New York Times, October 23, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/23/arts/television/ken-burns-american-revolution.html.

[2]. Kevin M. Levin, “Using Ken Burns’s ‘The Civil War’ in the Classroom.” The History Teacher 44, no. 1 (2010): 9–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25799393.

[3]. Special thank you to the Department of History and Philosophy at Kennesaw State University, which arranged screenings on campus of The American Revolution on five consecutive nights.

[4]. The book reminded me in many ways of H. W. Brands, Our First Civil War: Patriots and Loyalists in the American Revolution (Penguin Random House, 2021).

[5]. For example, Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (University of Georgia Press, 2024); Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782 (University of South Carolina Press, 2008); John Oller, The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution (Hatchette Book Group, 2016); Walter Edgar, Partisans & Redcoats: The Southern Conflict That Changed the Tide of the American Revolution (HarperCollins, 2001).

[6]. Ken Burns, quoted in Vanessa Armstrong, “Ken Burns Says His New Documentary Forced Him to Revisit Everything He Thought He Knew About the American Revolution,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 13, 2025, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ken-burns-says-his-new-documentary-forced-him-to-revisit-everything-he-thought-he-knew-about-the-american-revolution-180987667/.