Last week, I returned to Charlottesville for a class at the Rare Book School on the University of Virginia’s campus. While in the area, I visited James Madison’s Montpelier, the site of James Monroe’s Highland, and the ruins of Barboursville, a house designed by Thomas Jefferson.

On my trip to Rare Book School last year, I visited Jefferson’s Monticello, Poplar Forest, and, of course, the University of Virginia. Additionally, I wrote an essay reflecting on these homes and Thomas Jefferson’s complicated life.

Part 1: James Madison’s Highland

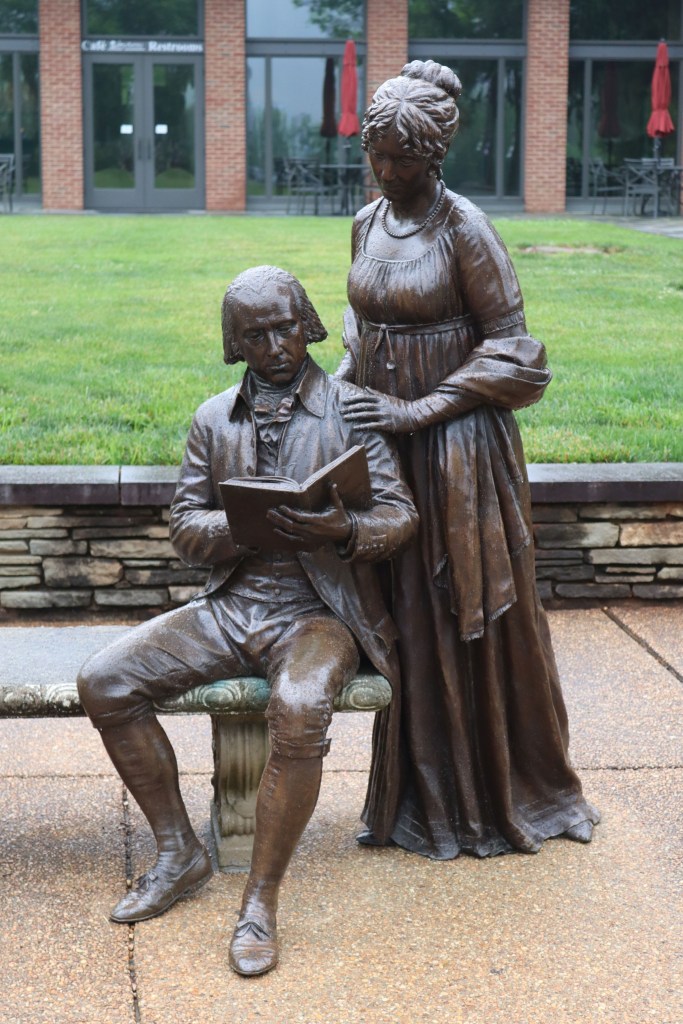

Of the presidents who have lived in the Charlottesville area, James Madison is one I know the least about. The “Father of the Constitution” moniker is memorable, as is his wife, Dolley, the “first First Lady.” (I did make sure to get a Madison biography at the gift shop!)

When Madison was born in 1751, his family’s plantation was known as Mount Pleasant. In the 1760s, they moved to a newly constructed home nearby, which they named Montpelier. Madison’s parents and James Madison himself would expand the house several times. When facing the front of the home, the original portion is on the right side of the portico.

On the guided tour of the house, we first entered through that door on the right side of the home, into the oldest portion. The door leads directly into a small hallway, showing the narrowness of the house. It is two rooms wide in most portions, though some rooms (like this hallway and the parlor) run almost all the way from the front of the house to the back.

Inside, our tour began in the rooms on the right, which are decorated as the home might have been in the 1760s. The front room was used by Madison’s mother (who died in 1829), while the back room was a small breakfast room. The house is decorated with a variety of period furniture, with only a few pieces, such as the face of the grandfather clock, original to the Madisons.

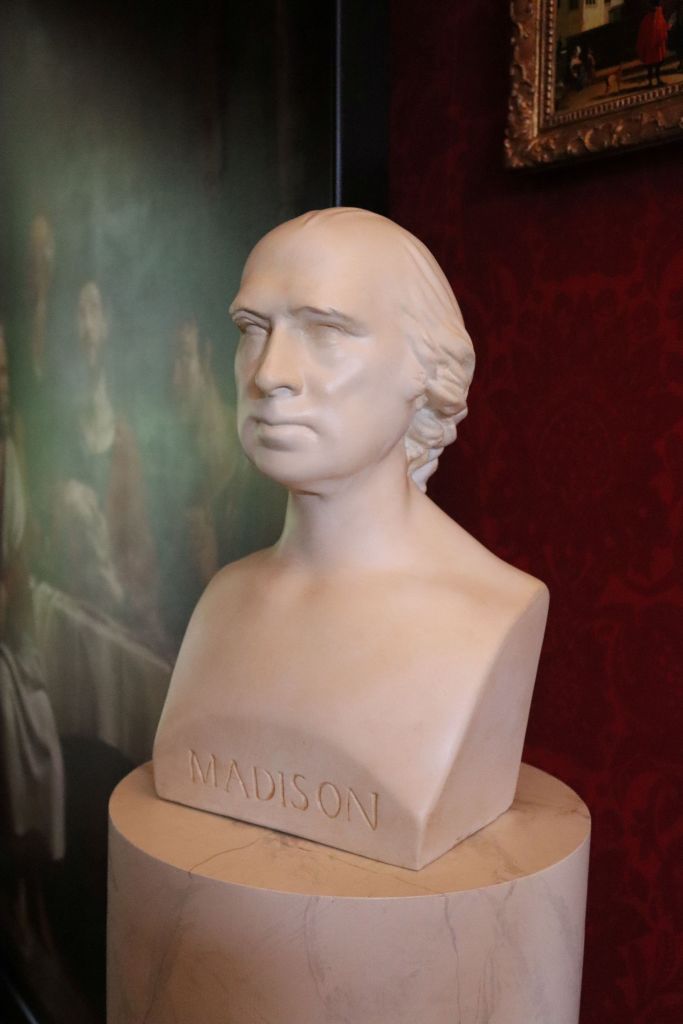

The parlor was used for entertaining guests and has several mementos to bolster Madison’s credibility as an educated statesman. For instance, busts and paintings of notable American and European figures are displayed throughout the room. A copy of the Declaration of Independence hangs above the fireplace, and a clock with Washington – “first in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen” – sits on the mantel.

The third image in the slideshow above shows an odd device with little self-evident purpose. Guests would sit on the side with the metal ball, and Dolley Madison would sit on the side with the crank. When Dolley turned the crank, it would shock dinner guests with a jolt of electricity as a parlor trick. Anecdotes like this make it easy to remember Madison was a close friend and ally of Thomas Jefferson.

The dining room is decorated as it might have been when the Marquis de Lafayette visited in 1824 and 1825. He was on his grand tour across the country he had supported almost fifty years before. In the dining room, Dolley Madison sits at the head of the table, as she was a much better conversationalist than her husband. Lafayette is at the other end, with Madison seated in the middle.

The black man serving the dinner guests is Paul Jennings. The Madisons owned around 100 enslaved men and women at any given time. Paul Jennings was born enslaved at Montpelier, worked at the White House for both the Madisons and James K. Polk, was sold by Dolley Madison after James’ death, and was able to purchase his freedom from Daniel Webster. Jennings was one of the few enslaved individuals from Montpelier able to gain his freedom. Interestingly, he is also the author of the first White House memoir. It was also his job during the burning of Washington to save the Lansdowne portrait of Washington from the White House.

During our tour, slavery was a significant topic of discussion in the dining room. Madison’s father, James Madison Sr., was allegedly poisoned by some of the enslaved men at Montpelier. Dolley Madison would sit at the head of the table closest to the kitchen stairway so that she could hear what was happening downstairs, and possibly find out about other poisoning plans.

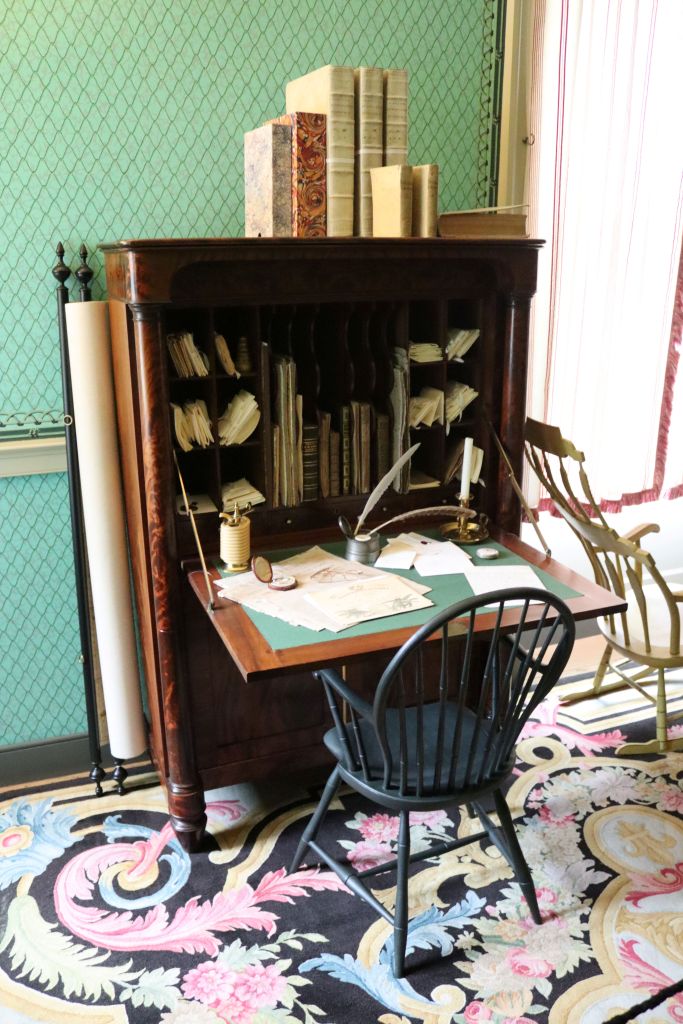

The library at Montpelier was somewhat spartan when it came to books, but it did have a nice map of Virginia. Inside this room, Madison compiled his notes from the Constitutional Convention of 1787 for publication, a project he would not live to see completed.

The parrot in the window represents Dolley Madison’s pet parrot, Polly. Polly lived in the White House, was known to swear, and once bit James Madison’s finger, exposing the bone. Interestingly, the Madisons were not the only White House occupants with a swearing parrot – Andrew Jackson’s parrot had to be removed from his funeral for excessive swearing.

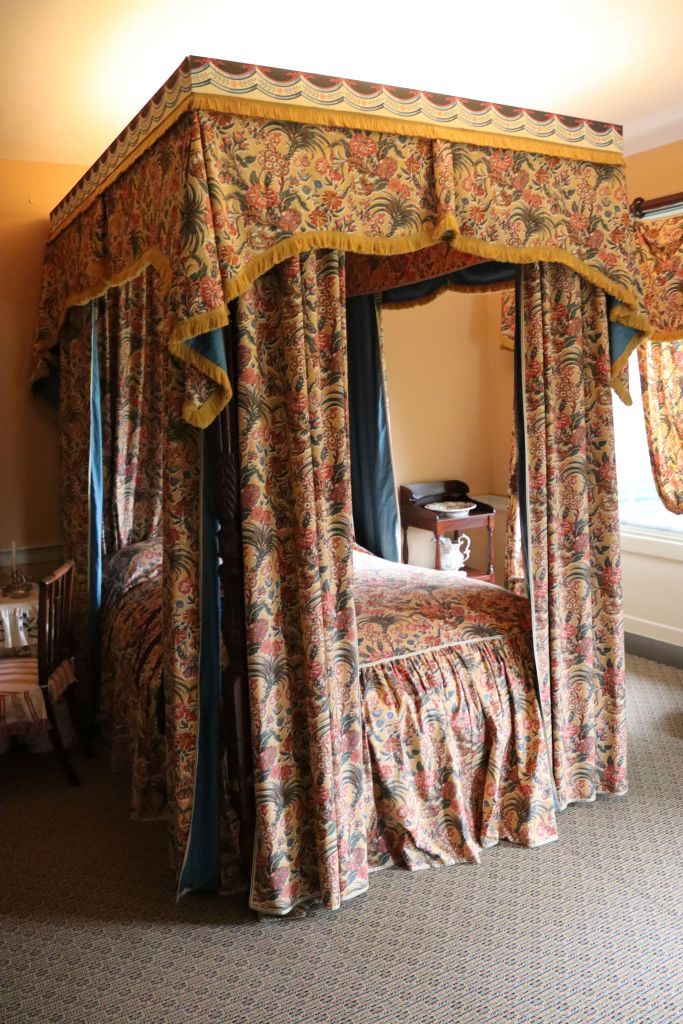

Inside this room, James Madison passed away in 1836. Originally used as a sitting room, it was converted into Madison’s bedroom as his health began to fail. The only first-hand account of his final day comes from Paul Jennings, his enslaved manservant mentioned earlier.

This upstairs room was used by Dolley Madison as her bedroom. After James’ death, Dolley moved to Washington and sold Montpelier in 1844. She would remain an important fixture of Washington society until her death in 1849.

This last room on the tour, the old library, is perhaps the most significant space at Montpelier. Inside this room, surrounded by books shipped from France by Jefferson, Madison wrote his original draft of what would become the US Constitution. This, more than anything else, is what makes Montpelier a truly important historic site.

Much like Poplar Forest, Montpelier has a room devoted to the restoration of the house. After Dolley Madison sold the house in 1844, it passed through a series of owners before being purchased by William and Annie duPont. The duPonts (covered more extensively below) made significant changes to the house, which have since been undone by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

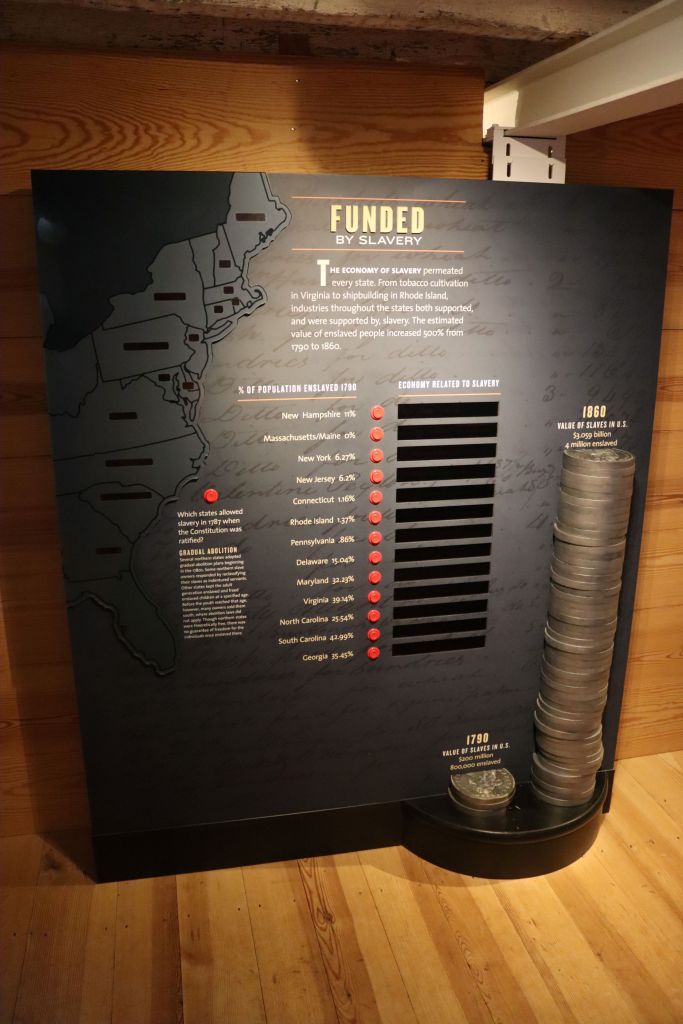

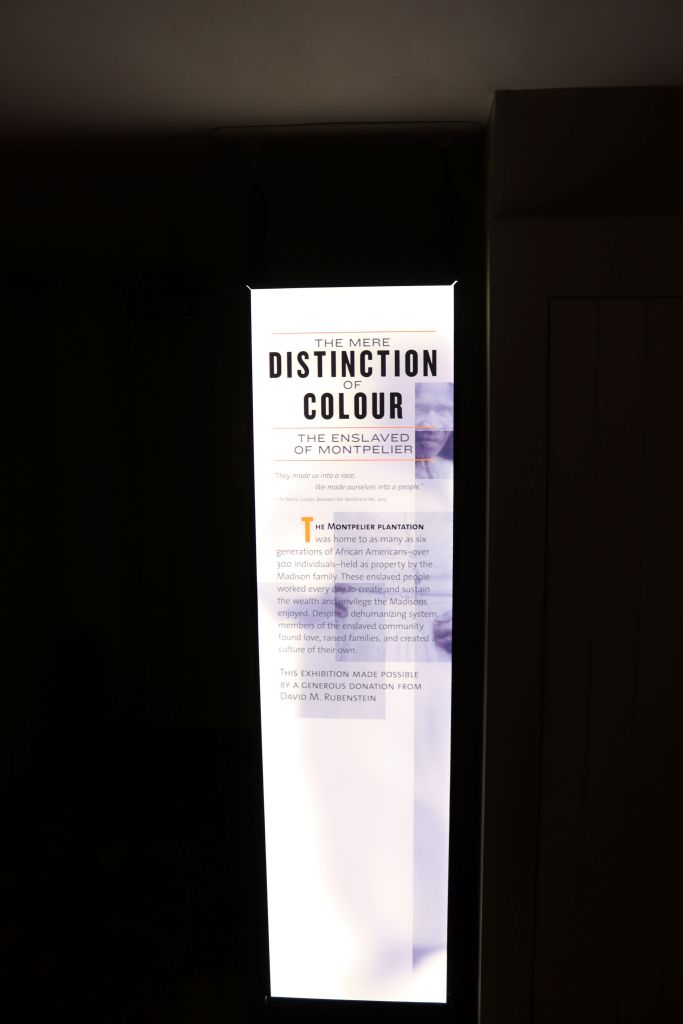

The cellar of the house features two exhibit spaces dedicated to the enslaved men and women of Montpelier. The first highlights those who worked for the Madisons, both at Montpelier and elsewhere. It also focuses on the connections enslaved individuals made between Montpelier and other neighboring communities.

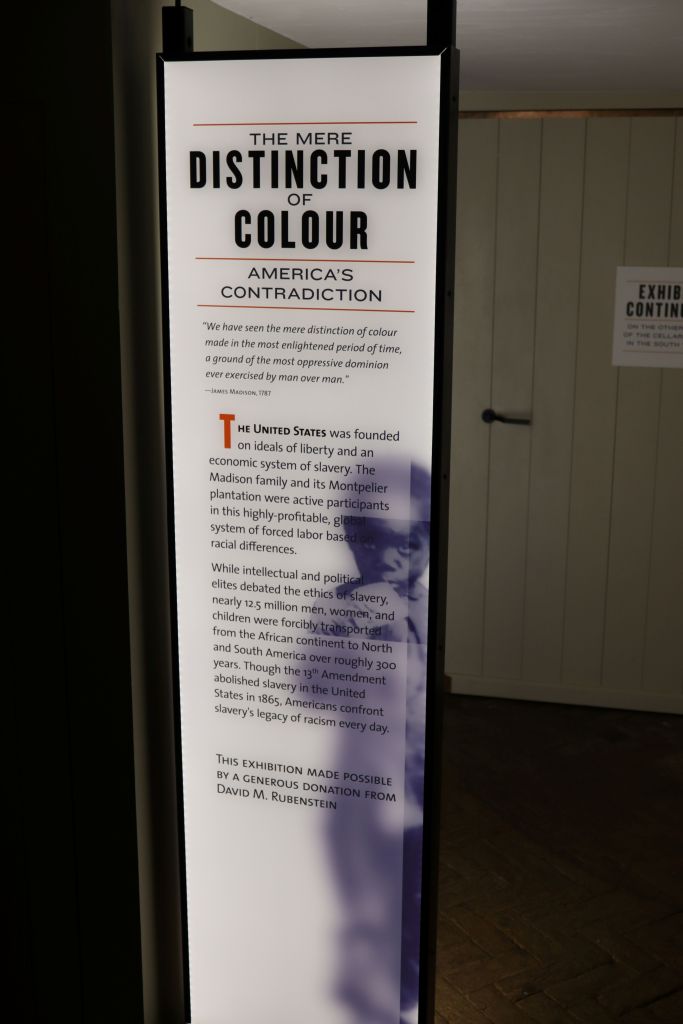

The second exhibit space, located on the other side of the house, offers a broader perspective on slavery as a whole. James Madison’s complex views of the subject are explored, along with slavery in the Constitution and constitutional law. Lastly, but not least, the exhibit examines the legacy of slavery today.

In the yard adjoining Montpelier are reconstructed slave cabins. The cabins painted white represent those that would have been on this site, while the more rudimentary log cabin would have been out in the fields. Inside are exhibits about life in Montpelier’s enslaved community.

Madison’s Montpelier is not the only presidential home to confront slavery, but it has done so in a very interesting way. The house is supported by the Montpelier Foundation and owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Additionally, there is a Montpelier Descendants Committee, composed of descendants of those who were enslaved here, many of whom still reside in the area. In 2022, the Foundation and Descendants committee merged, as a way of ensuring the story of all who lived at Montpelier is shared, not just the owners of the house.

The grounds of Montpelier have many features not present when the Madisons were here. These include the gardens built by the duPonts, various outbuildings built by previous owners (including what is likely the South’s oldest private bowling lane), a horse racing track, and a train depot from 1910 that now houses a civil rights museum.

At the front of the house is Madison’s Temple, a simple circular building that once sat at the end of a landscape feature called Pine Alley. It was inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Rome and was built around 1810. Below it was an icehouse.

The last feature of Montpelier’s grounds is my favorite. Located near the site of the Mount Pleasant plantation is the family graveyard, which serves as the final resting place of both James and Dolley Madison.

At the Montpelier visitor center, there are two main exhibits plus a gift shop. It is named after David M. Rubenstein, the philanthropist who is also the namesake of Monticello’s visitor center. Inside are two murals: one of Madison at the Constitutional Convention, and one of Dolley Madison evacuating the White House during the War of 1812.

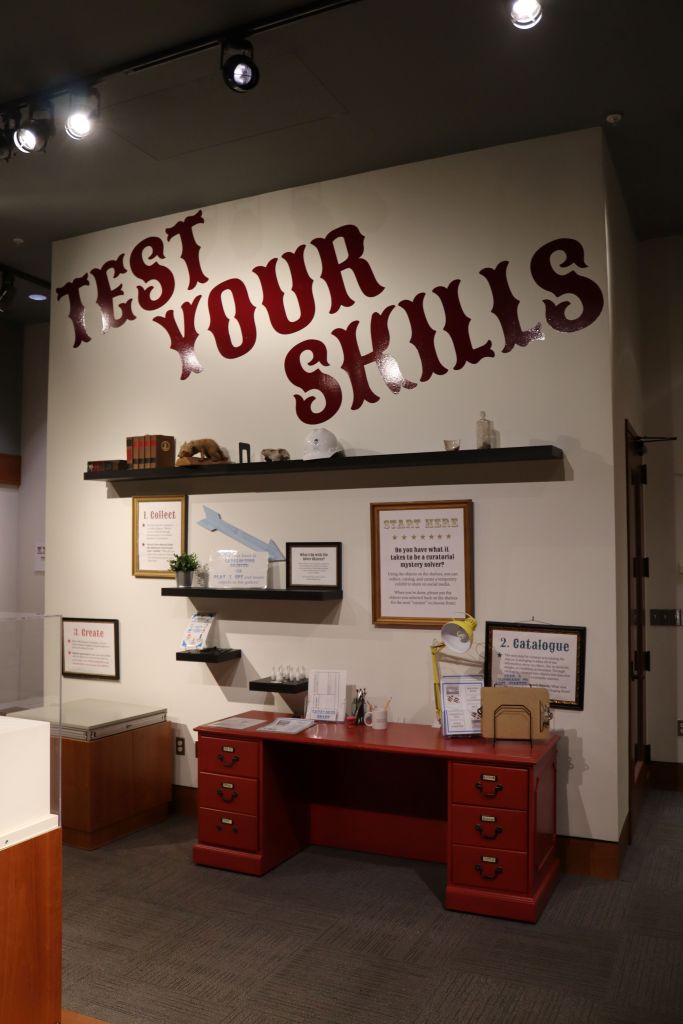

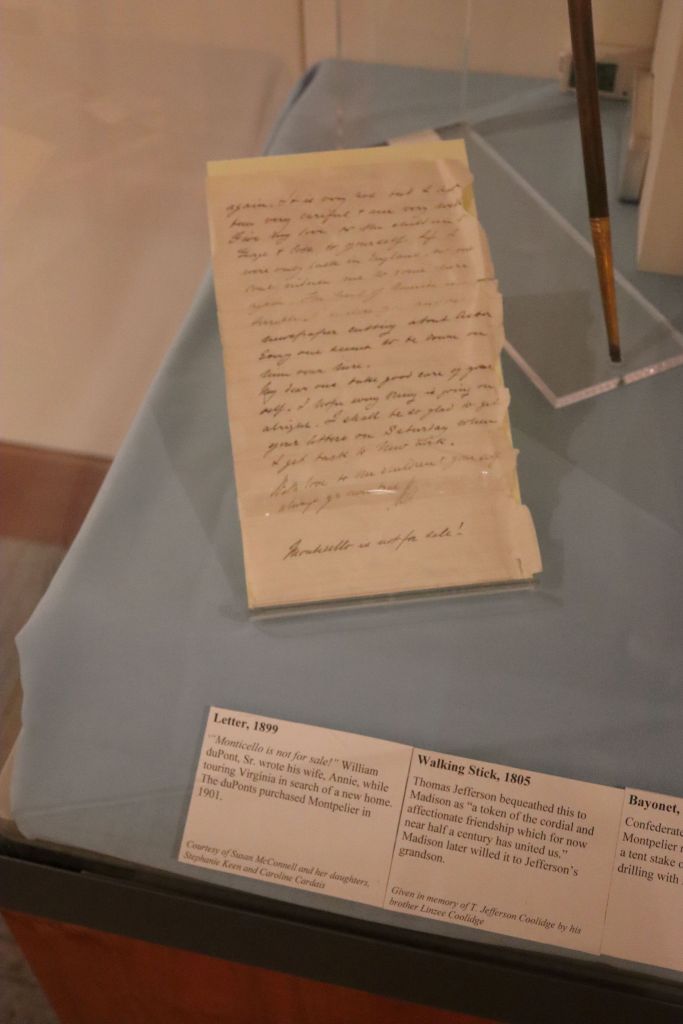

The first gallery is about artifacts of Montpelier and the process of curation. Aspects of it seemed aimed toward younger audiences, though this room also had some fascinating artifacts. Among these were a portrait of Dolley Madison, an engagement ring she wore from the 1790s until her death, stamps from Montpelier Farms, and a duPont letter about how they tried purchasing Monticello before Montpelier.

The second gallery explored the duPont’s time at the house. They owned the house from 1901 to 1983 and made significant additions and renovations. Most noticeably, they added around fifty rooms and stuccoed the exterior. The house was given to the National Trust for Historic Preservation so that it could be returned to the Madison-era appearance. The project would not be completed until 2008.

One of the more unusual parts of this exhibit was the Red Room. In the late 1920s, Marion duPont Scott remodeled one of the rooms with a red and chrome Art Deco design. Throughout the room were photos of her beloved racehorses. In 2004, when the house was being restored, the entire room was disassembled and relocated to the museum.

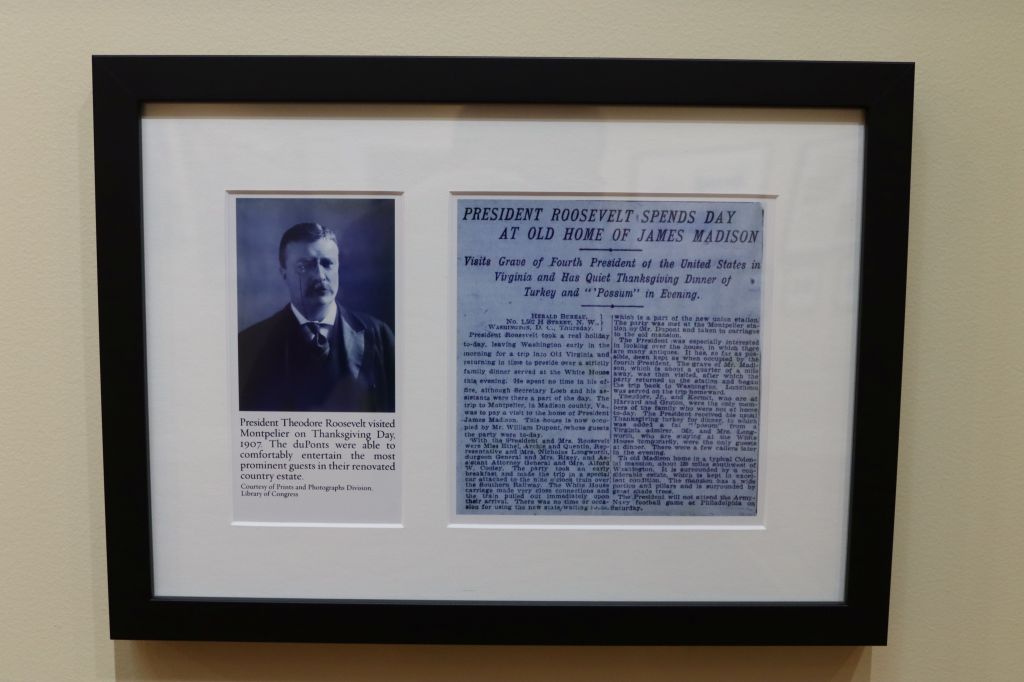

Last, but not least, I have to throw in the obligatory Theodore Roosevelt connection. He visited the home in 1907.

James Madison’s Montpelier was fascinating for several reasons. Like Monticello, it is interesting to see how the site today grapples with the issue of slavery. The inclusion of their descendants on the Foundation’s board is a unique and admirable approach. I was surprised that there was no gallery dedicated to the lives of James and Dolley Madison, though much of their story was shared while walking through the house.

Across the museums and grounds, there is a lot to see from when the duPonts owned the house, showing their lasting impact. I recall only scattered references to the Levys at Monticello, who owned the home for much of its history. The way the post-Madison history of Montpelier is presented is reminiscent of Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, which also has a story of continual change and then restoration.

Part 2: Barboursville

James Barbour served as Governor of Virginia from 1812 to 1814, served as a senator from 1815 to 1825, and was John Quincy Adams’ first Secretary of War. After finishing his term as governor, Barbour asked his friend Thomas Jefferson to design a Palladian home for him. The house was finished around 1822 and named Barboursville. It bears a striking similarity to Monticello, though it is significantly smaller. A dome, much like the one at Monticello, was planned but never built.

On Christmas Day in 1884, the house was destroyed in a fire. All that survived were the brick walls and columns, which are now preserved at the Barboursville Vineyard. Adjoining the house are two contemporary brick cottages now used as a bed and breakfast.

While on our way to Montpelier, we happened to see a road sign about the ruins. As we made our way back to Charlottesville, we decided to stop. The ruins are completely free to visit.

Peering inside Barboursville, it is easy to see how the house was originally constructed: the ghost of a staircase can be seen in the plasterwork, the brick of the columns is exposed, and the fireplaces are open to the elements.

James Monroe’s Highland

While I knew very limited details of Madison’s life before visiting his home, James Monroe is an individual I was more familiar with, largely thanks to Tim McGrath’s biography of the fifth president.

A native of Virginia, Monroe served in the Continental Army during the Revolution and is holding the American flag in Emanuel Leutze’s famous Washington Crossing the Delaware painting. He would later serve concurrently as Secretary of War and Secretary of State and was elected president in 1816. He served two terms.

Highland was purchased by James Monroe in 1793 and was sold in 1825. Though it was technically their primary residence for years, the Monroes visited very infrequently, instead living in Washington or overseas when Monroe was an ambassador. Where Jefferson and Madison had large, brick plantation houses, Highland was a small wooden structure.

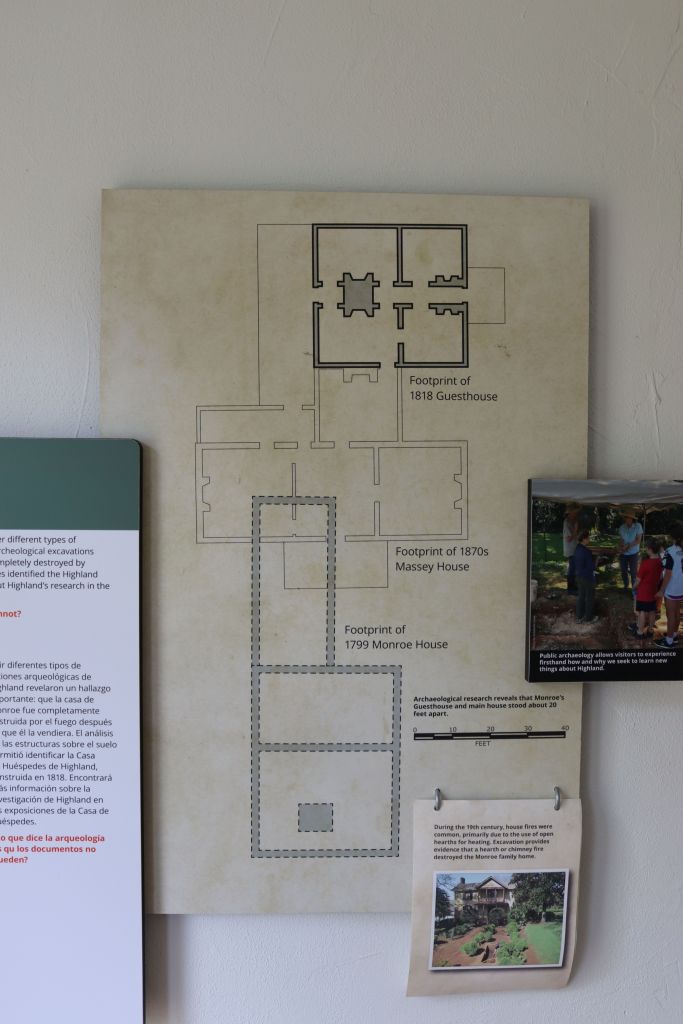

At an unknown date, Highland was lost in a fire. The property would change hands several times before being acquired by the College of William and Mary in 1974. The house site is today an archaeological site. Stones in the yard show the outline of Monroe’s house.

Though the main house is long-gone, several structures from Monroe’s era still stand. The smokehouse is the oldest structure on the property (I believe our guide said it was c. 1790s), while the nearby overseers’ house was built around a decade later.

When the Monroes were away from home, they hired an overseer to manage the plantation’s enslaved population. The plantation here was significantly smaller than Monticello or Montpelier, with only around 50 enslaved laborers living there at a time. Even still, this made Monroe was one of the largest slave-owners in Albemarle County.

The enslaved population at Highland would have lived in dwellings similar to those at Montpelier. A few lived closer to the house, in a duplex-style building. While that structure was removed years ago, a reconstruction has been built more recently. It is home to exhibits about how to uncover the story of a house no longer standing.

Highland is not home to an exhibit dedicated solely to slavery, though that history can be found throughout several exhibits. Interestingly, Highland is the only house museum I have been too with exhibits in two languages, English and Spanish.

The other building at Highland, originally built for the Monroes, is the guest house. Built in 1818, this structure was initially separate from the main house. After the Highland house burned, its later owners used it as the main house and gradually expanded it.

The main entrance to the 1818 guest house is actually an expansion dating to the 1820s. Inside the upper levels of the guesthouse are exhibits on the archaeological digs at Highland and what it was like to visit the Monroes house.

Several pieces of furniture in this space are original to the Monroes, including a sofa they purchased in France in 1803.

One smaller piece of the house was added in the 1850s. This section is devoted to Monroe’s time in France, when James Monroe arranged the Louisiana Purchase. The room is decorated like the rooms Monroe may have rented in Paris, and features a bust of Napoleon.

In the 1870s, the Massey family owned Highland and built a new main house. Now painted yellow, it stands out clearly from the other buildings on the property. Part of this house was built on top of where Monroe’s main house once stood. One room of the Massey house is used as a museum on the Monroes, while the rest of the house is closed to the public.

It was fascinating to see how the story of Highland is shared, even with Monroe’s house no longer standing. Monroe felt a great affection towards Thomas Jefferson, and the close proximity of Highland and Monticello shows this well. The other major Monroe Museum is located in Fredericksburg, and I am curious to know if there are differences in how Monroe’s life is presented at these two sites.

Interested in subscribing to my blog? Type your email below to be notified about new posts.