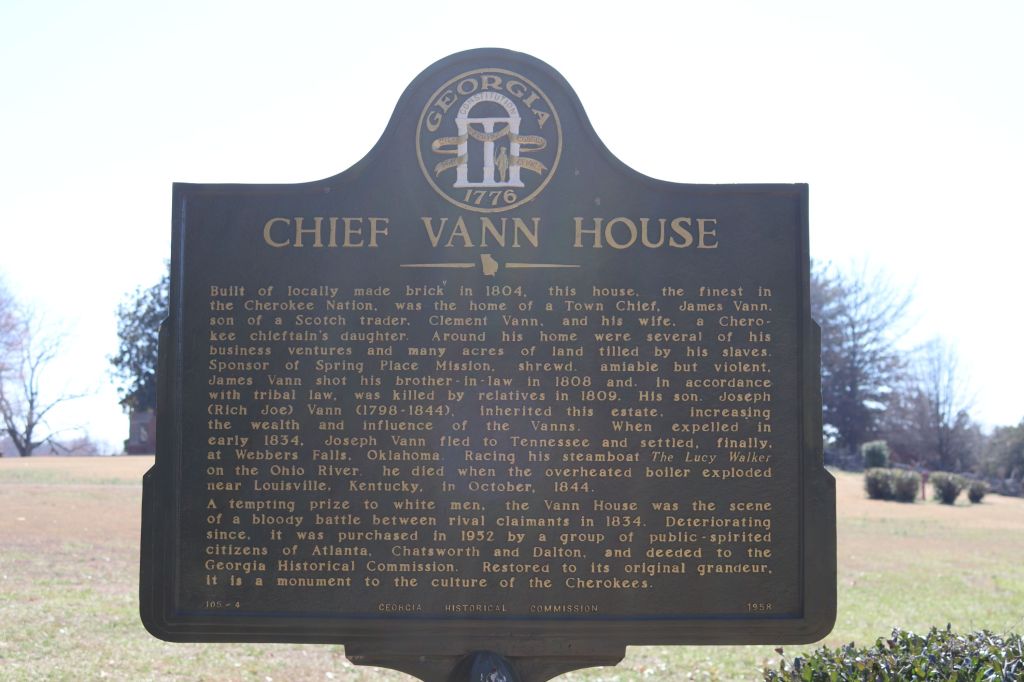

When the Chief Vann House in Murray County was built, it was the first brick house in the Cherokee nation. It was built by enslaved laborers around 1804 for James Vann, and his son Joseph owned the house at the time of the Trail of Tears. Since the 1950s, it has been preserved by the state as Chief Vann House Historic Site.

Image: “Rear Entrance, Chief Vann House” by Cline Photo, Inc., published by Color-King (after 1958).

Yesterday (February 14, 2025), I visited the Chief Vann House. Below are photos from my visit. All of these were originally published on my Peach State Past site.

There is some debate about when the Chief Vann House was built. The traditionally accepted date is 1804, when James Vann was known to have completed a house. However, others believe it was built later by Vann’s son Joseph on the same site as the 1804 home. It was designed by a German architect and sat at the heart of a massive plantation. James and Joseph were among the wealthiest men in the South when they lived here.

The house itself is located in Murray County, between Dalton and Chatsworth. In Vann’s day, it was along the Federal Road, a major thoroughfare that passed through the Cherokee Nation.

Our tour started inside the museum, where there is a short fifteen-minute film about the house’s history. There is also an exhibit room with artifacts from the Vanns and the Cherokee. One of the most interesting artifacts is the original land lottery deed used by White settlers to take possession of the Vann’s land.

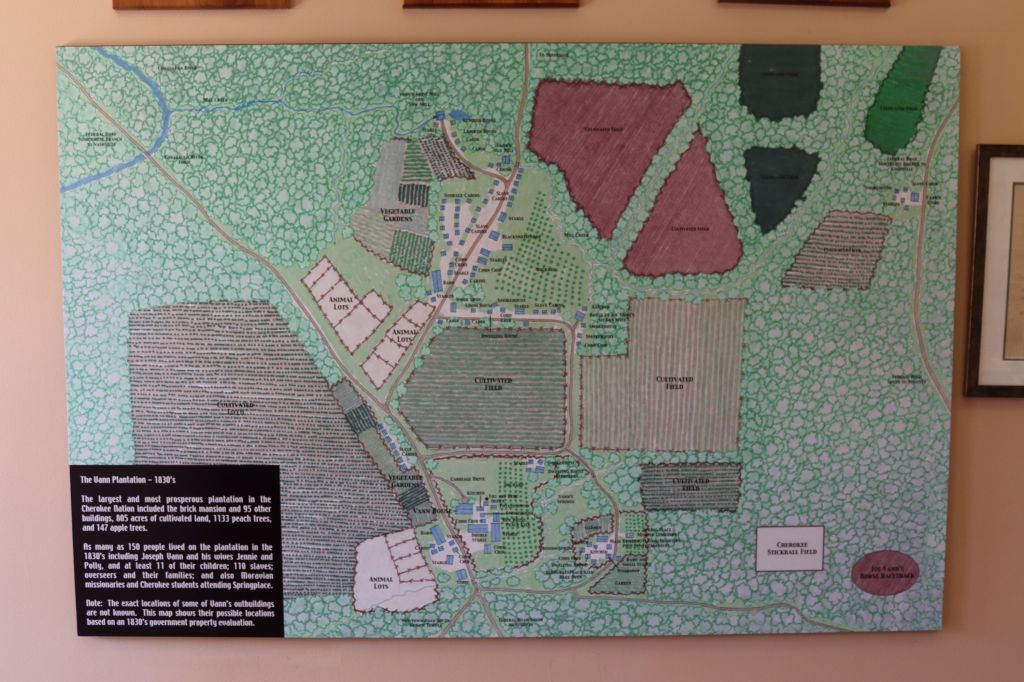

Inside the museum is a map of what the Vann’s plantation may have looked like. There is also a model of the house and surrounding barns and slave cabins, along with the Moravian Mission that the Vanns supported nearby.

The entrance hall of the Vann House is dominated by a staircase that almost seems to float suspended in the air (though it has received additional support from an added column since the 1990s). Unfortunately, I did not get a good photo of it on the main level, so a photo from the second will have to suffice. I was able to get good photos of its detailed woodwork.

On the left side of the house is the dining room, which features one of several impressive fireplace mantelpieces. Above it is a portrait of Joseph “Rich Joe” Vann. His father, James Vann, was assassinated in 1809, and Joseph inherited his father’s vast fortune. In 1834, he was thrown out of his mansion and was forced to move to Oklahoma. He died in a steamboat explosion in 1844.

Opposite the dining room is the parlor. The mantelpiece in this room is the home’s most elaborate. All of the colors in the house are what the Vanns used. The original paint was uncovered in the 1950s (under almost 20 layers of paint) and replicated for the home’s restoration. According to our tour guide, legend says this mantelpiece once had animals carved on it, but they were removed by a later owner of the house.

When white settlers threw the Vann’s out of their house, they fired shots inside the home and threatened to burn it down. They went so far as to bring a burning log into the house, and you can still see burnt spots on the staircase.

Directly above the parlor is the guest bedroom. Several notable guests are known to have stayed at the house, including James Monroe. He visited in 1819 while touring the South.

Directly above the dining room is the master bedroom. A small picture of Joseph Vann hangs on one of the walls. The Vanns bred racehorses, which are represented in paintings on the walls.

The attic of the house was used in the winter as the children’s bedroom. Because of the heat, they likely slept on the porch during the other seasons of the year. The attic is very short, with six-foot ceilings.

The final space inside the house is the cellar. There are two spaces, one used for vegetables and a darker, colder space for meats and alcohol.

The rear of the house, with its asymmetrical porch, is a bit more distinctive than the front. This is also the side first seen by visitors coming from the interstate.

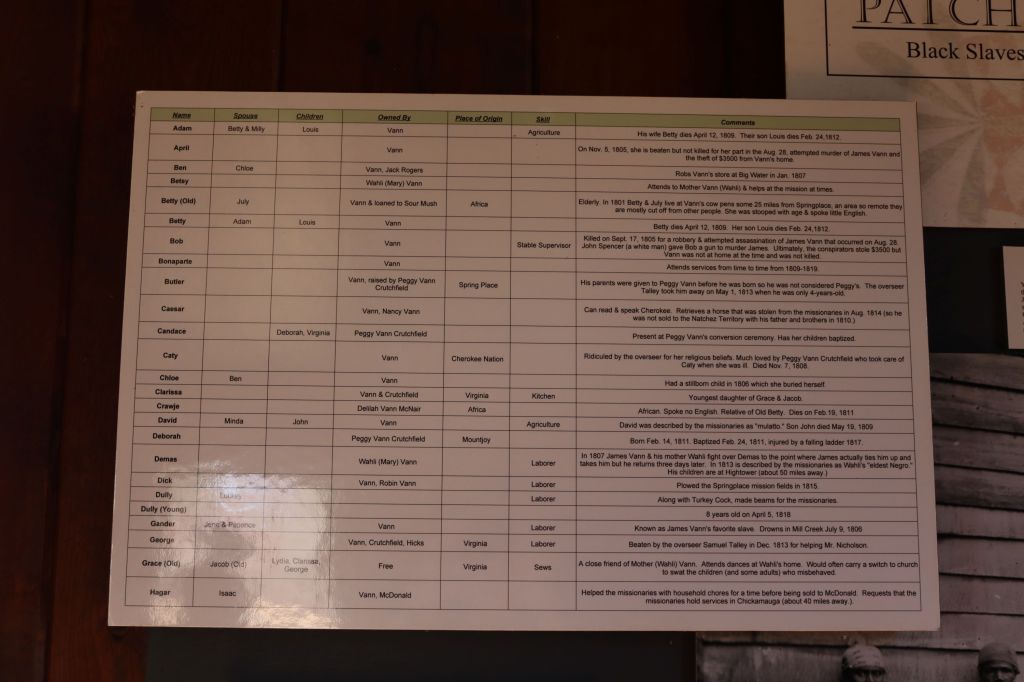

Adjoining the Chief Vann House is a reconstructed workhouse and kitchen. Inside are exhibits on slavery among the Cherokee. The Vanns’ plantation had over 100 enslaved laborers. Several exhibit panels highlight the stories of the known individuals, using records of the nearby Moravian mission.

The final few buildings at the Vann House are original Cherokee log structures. These 1830s structures were moved here from across North Georgia in the early 2000s.

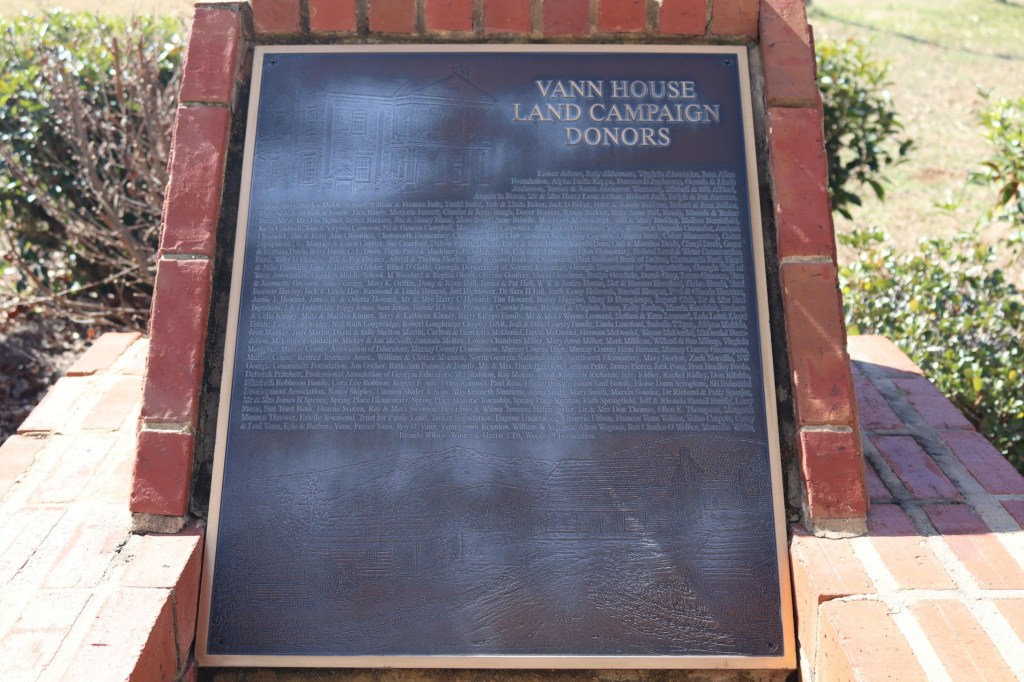

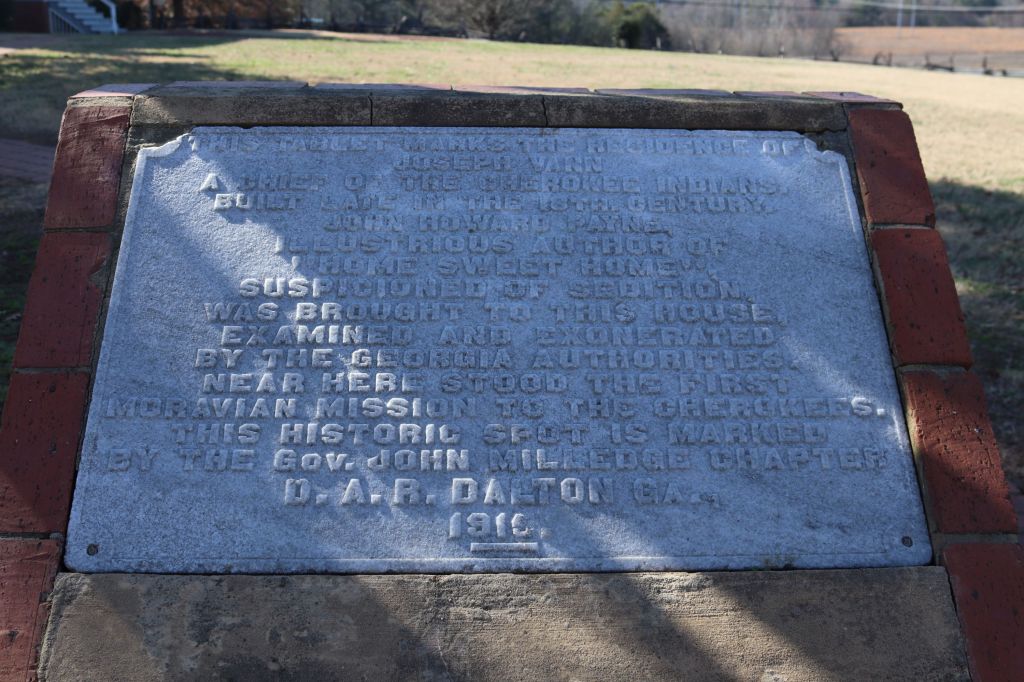

Countless historic signs and markers can be found throughout the Chief Vann House grounds. To conclude my photos from the historic site, here a just a few of those signs.

During the pandemic, I did a video on the history of the Chief Vann House as part of my series on Georgia’s state parks.

For more information on the Cherokee in North Georgia, check out this recent blog post of mine on Cobb County.

For the story of the Trail of Tears, see Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation by John Ehle.

Interested in subscribing to my blog? Type your email below to be notified about new posts.