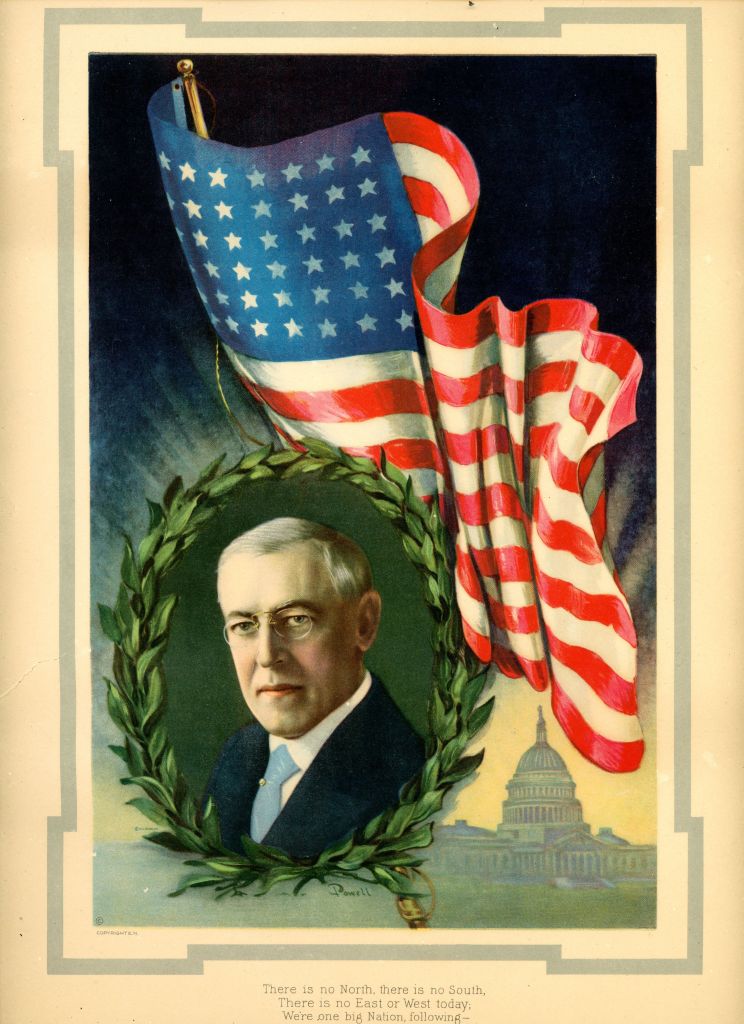

I am a fan of presidential history, and I am a fan of classic movies, so I was surprised to realize that these two interests have rarely overlapped. (All the President’s Men and 1776 are the exceptions.) This week, I found out about a box office bomb presidential biopic I was unaware of, Henry King’s Wilson from 1944. As someone who loves not just classic movies, but also bad movies, I had to see Wilson for myself.

Dominating the film is Alexander Knox, who plays Woodrow Wilson, often cool and collected but prone to moments of heightened emotion. At points, Wilson can feel a bit stiff and flat, which in fairness seems true of the real Wilson as well. It also covers well his two marriages, with both Ellen and Edith Wilson taking important roles, but the rest of his family does not feel fleshed out. It is also obviously made for World War II audiences, but I can not help but wonder if it was released too late. As propaganda, Wilson’s speeches assailing isolationists seem like they would have been more effective if it was released before the war’s start.

The action begins with Wilson at Princeton University, a professor largely uninterested in entering the political arena, being approached by powerful politicians about running for Governor of New Jersey. This early into the movie, one of its largest flaws begins to appear. The story of Wilson largely glosses over real critique of most of his life and actions. He left Princeton in 1910 after debates over where to place the Graduate College effectively ended his presidency. Crucially, he also had few hesitations about entering politics.

After being elected Governor, Wilson’s supporters begin to push for him to run for president. After an eventful 1912 Democratic National Convention, Wilson is nominated on the forty-sixth ballot. His opponents, Republican candidate William Howard Taft and Bull Moose Theodore Roosevelt, are occasionally mentioned throughout the rest of the film. Neither of these candidates is portrayed by an actor in Wilson, though one vaudeville performer is shown dressed as Roosevelt in blackface. The odd scene is one of the few times race is addressed in the film, and it seems to hint at Wilson’s well-known racism, though the film hardly seems to condemn it.

After the election, there is a brief montage of Wilson’s signing various legislation making up his first-term accomplishments. From here, the political aspects of the film turn away from his domestic policy, and it is never addressed again beyond passing remarks again. Wilson’s foreign policy – World War I, the Fourteen Points, the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations – dominate the rest of the film. Because of this, it is hard to get a sense in Wilson of the subject’s political beliefs.

Wilson’s family plays a significant role in the movie, with the sub-plot of Ellen Wilson’s death and Woodrow’s marriage to Edith being an important part of the movie. His three daughters all appear, though it can be hard to tell them apart. William G. McAdoo (portrayed by Vincent Price!), also appears several times throughout the movie. However, quite oddly, the film neglects to mention his 1914 marriage to Wilson’s daughter Eleanor.

World War I overshadows the movie, and Wilson is depicted as an interventionist waiting to enter the war when the time is right. Debates about intervention are also included, with different citizens arguing for and against going to war. There is also a scene where Wilson’s cabinet, after the Lusitania’s sinking, encourages a declaration of war. No one in the cabinet argues isolation is best. In real life, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan was opposed to entering the war on the side of the allies. Bryan would resign from the cabinet in 1916. While his character is present in Wilson’s cabinet meeting, he is not a voice of dissent. After this scene, Bryan does not appear again, and the resignation is not addressed.

Except for a scene where Wilson is serving soldiers with the Red Cross, World War I is represented by a series of edited newsreels. The footage depicts everything from the trenches of Europe to Mary Pickford selling Liberty Bonds. Wilson returns to present the Fourteen Points, then goes overseas to Europe. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who appears sporadically in the preceding parts of the film, begins to become a more important character. At Versailles, Wilson’s arguments in favor of self-determination sound very reminiscent of FDR. Wilson returns home to find a block of Congress, led by Senator Lodge, opposed to his League of Nations.

Wilson next begins a tour across the United States to save the League, but after a speech in Pueblo, Colorado (where he predicts a second World War without the League) he collapses and is unable to resume the journey. Doctors advise it would be detrimental to his health to resign. In real-life, Edith stepped in, and many have claimed she served as a de facto president. Wilson shows her reluctant to take on the mantel, and there is a comment about her consulting the president on everything. One of the last scenes of Wilson in office shows him disparaging the passing of the Volstead Act over his veto. This section of the film largely reflects Edith Wilson’s version of what happened. Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper Jr. notes that much of what Edith later claimed happened is suspect. For instance, the veto of the Volstead Act was likely a decision made “with Edith’s consent and without Wilson’s knowledge.”

The film ends with Wilson, debilitated by his stroke, learning his party has been defeated in the 1920 election. Wilson’s overall message seems to be about the importance of the League of Nations, and how it could have stopped World War II. For a movie released in the middle of that war, it is not surprising this is the focus. However, as a presidential biopic, I found it lacking. Maybe I am expecting too holistic an approach, but I believe a movie about the president should feature more exploration of his politics. Was he conservative, liberal, or progressive? Wilson seems uninterested. This lack of insight into Wilson’s political beliefs may be my largest issue with the film.

It is only fair at this point that I mention I do not like Woodrow Wilson. I appreciate his dedication to world peace, but on domestic policy matters I think he caused more harm than good. Much has been written about his racism, how he segregated the federal government, and his small part in the rebirth of the KKK. I find his often-overlooked attacks against Mexico overblown. I also don’t believe in his ideas about American Government. Wilson, before entering elected office, was a noted advocate of a system of government like the United Kingdom’s parliament, an erasure of the separation of powers. After the end of World War I, the Wilson Administration condoned several major violations of civil liberties. My dislike of Wilson may also be rooted in my respect for his political enemy, Theodore Roosevelt. Wilson overlooks these issues (and other matters, like his affair with Mary Peck), and the overly rosy view of Wilson is a jarring for me.

As much as I dislike him, I find him interesting for how he can divide opinion. My view of Wilson is completely at odds with those who compare him to Jesus (to pull from my bookshelf, Lucian Lamar Knight and A. Scott Berg). Wilson does not go that far, though it does try to connect him to Lincoln, and to a lesser extent Washington. Though it is subtle, I believe FDR was also on the filmmakers’ minds. Given Wilson’s Southern background and noted racism, Lincoln is an especially interesting comparison. (John Milton Cooper Jr. also compares Lincoln to Wilson, saying both were responsible for “massive violations of freedom of speech and the press.”)

Though I have difficulty with its overall message, there are places Wilson shines. The newsreel footage of World War I is admirably done, and does a better job representing the conflict than conventional narrative. I am also fond of the scenes at the Democratic National Convention. The conventions of this era were raucous, wild places, fit for film but rarely depicted. The parade for Champ Clark, the cheers for Underwood, and the dramatic speeches of Bryan capture the feeling well. After seeing these scenes, I sincerely believe a movie about a Gilded Age or Progressive Era national convention (maybe the 1880 RNC or 1912 conventions) would be immensely engaging.

The last area where the film succeeds is the “cameos” of historical figures. Some contemporary figures, like Henry Cabot Lodge, are essential to the story Wilson hopes to tell. Others, like William G. McAdoo, Thomas R. Marshall, Champ Clark, and Oscar Underwood are less necessary but still included. I wish some characters could have been featured more, like Robert Lansing, William Jennings Bryan, Colonel Edward House, and Thomas R. Marshall, but I have to admire the variety of figures included.

Wilson received five academy awards and was nominated five more, including Best Picture and Best Actor. Reviewers loved the film, but audiences were less enthusiastic. Studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, who considered the project his brainchild and baby, 0rdered that it never be mentioned in his presence. Winston Churchill left a screening early. It has gone down in Hollywood history was the biggest presidential biopic flop ever made. Overall, I would say the film is decent but not superb. Despite this, it remains a fascinating look at the mythology surrounding Woodrow Wilson, and to see what history made the cut and what was discarded.

Update 9/14/2024: I have finished reading American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild, and my opinion of Wilson has damaged further.

Several sources were useful in writing this review. Citations are included below.

Berg, A. Scott. Wilson. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013.

Cooper, John Milton Jr. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

Daniels, Josephus. The Life of Woodrow Wilson. Will H. Johnston, 1924.

Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Anchor Books, 2007.

Knight, Lucian Lamar. Woodrow Wilson: The Dreamer and the Dream. Atlanta: Johnson-Dallis Co., 1924.

Ruiz, George W. “The Ideological Convergence of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 19, no. 1 (1989): 159–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40574572.

“Wilson (1944),” IMDb, accessed September 2, 2024. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0037465/.

Interested in subscribing to my blog? Type your email below to be notified about new posts.

2 thoughts on “Wilson: An Idealist in a Less-than-Ideal Movie”

Comments are closed.