On July 7, I visited Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson. I took hundreds of photos, the best of which can be found below. I originally posted these on my Archive of the Past social media site.

The starting point at Monticello is the David M. Rubenstein Visitor Center. There is a theatre, exhibits, and a large courtyard. Up the grand steps are the shuttles to the house.

The museum at Monticello is divided into three galleries. The first of these covers the history of the house, including an earlier iteration referred to as Monticello I. The gallery features some of the original tools Jefferson used when designing the home.

The second of three galleries at Monticello focuses on the Declaration of Independence. The copy on display is an 1823 engraving by William J. Stone, one of only fifty of its kind in existence.

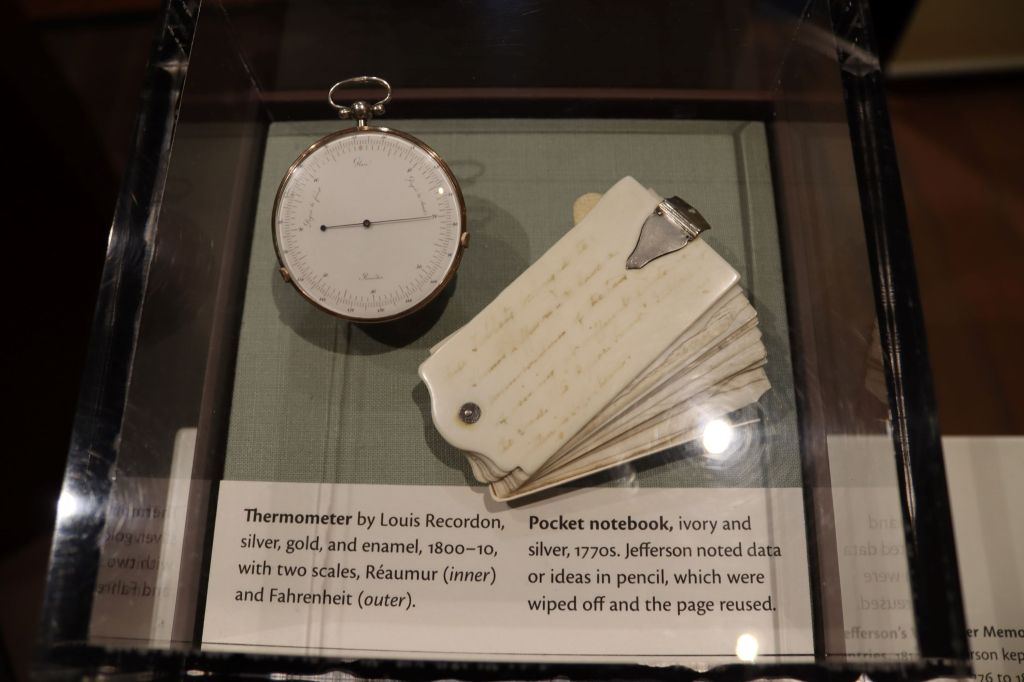

The third and final gallery at Monticello is all about life at the house and Jefferson’s intellectual ideas put into practice. This gallery has more information about Jefferson’s family at Monticello and the enslaved men and women who labored here. The exhibit notes that one item on display, a small jar with French writing, may have been owned by Sally Hemmings.

Riding on the bus to Monticello brings you to this side of the home. Just past the porch is the entrance hall. A couple days before this trip, we purchased tickets for the Behind the Scenes tour. This tour showed us more of the home than some of the other offerings.

The entrance hall to Monticello contains an eclectic mix of decorations, representing Thomas Jefferson’s very unique mind. The room is filled with paintings of classical scenes, souvenirs of Lewis and Clark’s voyage (recreated in recent years by Native American tribes, as the originals are lost), and American symbolism.

One of the sets of antlers on the right of the entrance hall

was collected by Lewis and Clark in 1803. It is one of the few remaining

specimens from that expedition.

For Monticello’s entrance hall, Jefferson chose four busts: himself, Voltaire, Turgot, and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was Jefferson’s political rival, so many visitors found him an odd choice. According to Thomas Jefferson, he placed the busts of himself and Hamilton on opposite sides so they could be opposed in life and death.

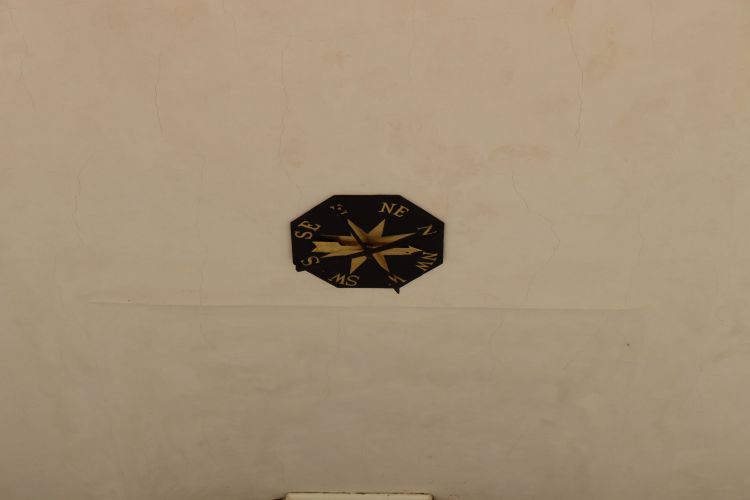

The clock in the Monticello entrance hall, which tells the time and day of the week, was designed before the room. It was found that the cannonballs that tell the day would descend too far, so a hole was cut in the floor. The sign for Saturday can still be seen in the basement.

Next door to the entrance hall at Monticello is a small sitting room. While the room was difficult to photograph with the bright light from outside, some of the details can still be seen. One of the prints on the wall is of Lafayette, who is depicted several times throughout the house.

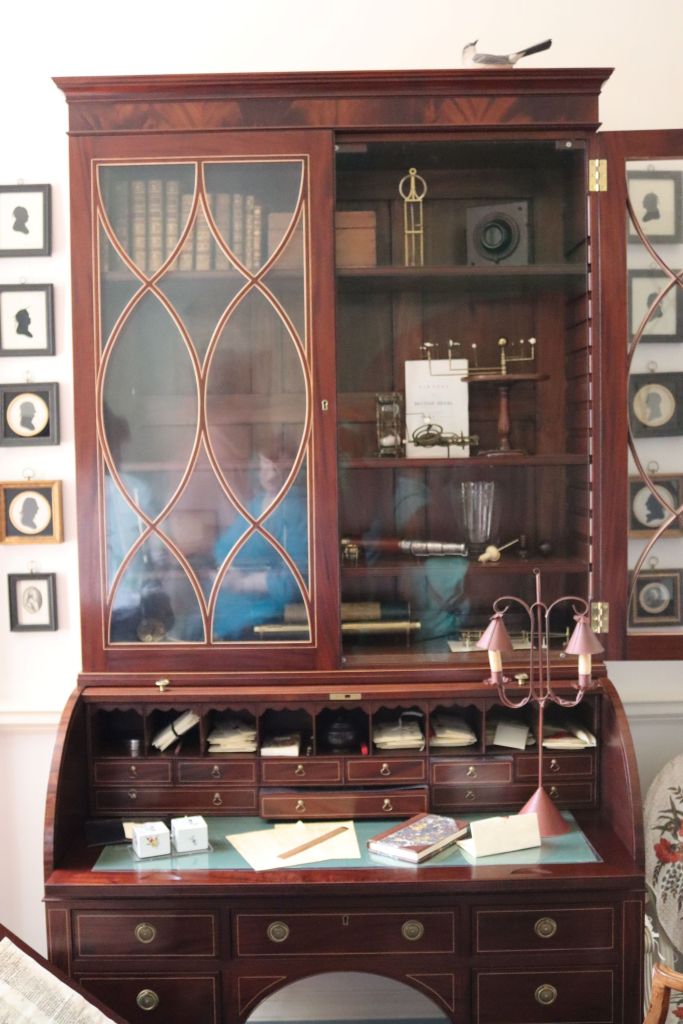

Thomas Jefferson’s library and office is in the corner of Monticello. He placed it very deliberately near his bedroom. The room is filled with books, scientific equipment, and drawing materials.

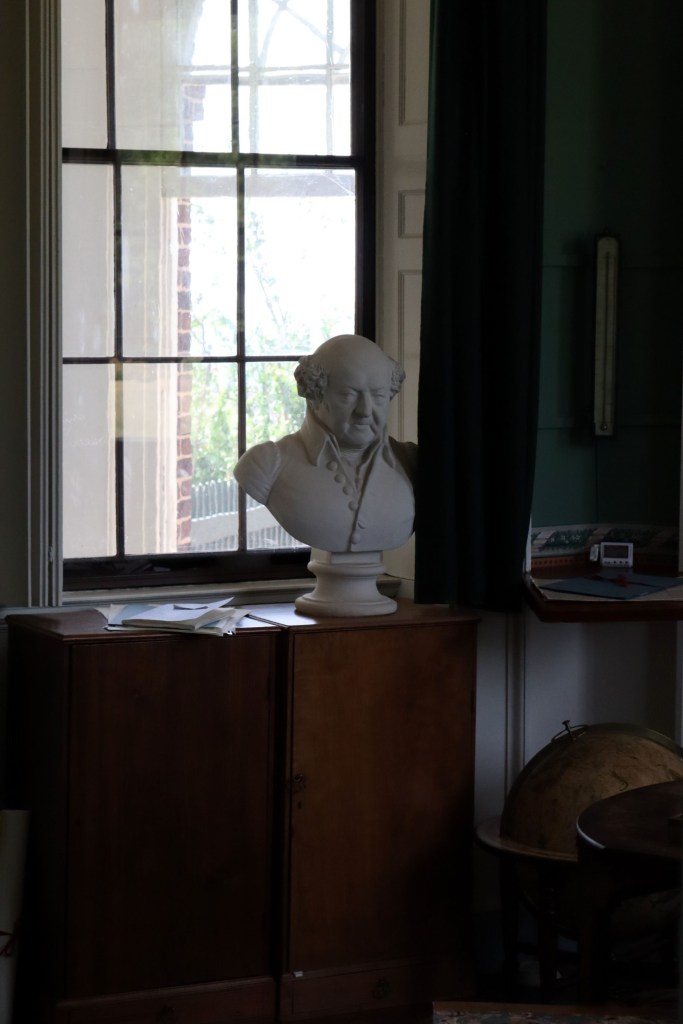

Jefferson’s office at Monticello continues into this small room. This space is easily accessible from his bed. Part of the decoration is a bust of his friend and political rival John Adams. The two died on exactly the same day: July 4, 1826.

It was inside this bed at Monticello that Thomas Jefferson died. The bed is inside an alcove inside a bedroom that Jefferson designed for him and his wife, Martha. Above the alcove bed is closet space. On display are many artifacts from Jefferson’s home life, including a locket with some of Martha’s hair.

The parlor at Monticello is where Jefferson liked to entertain. It is filled with curiosities, including a trick door, a vacuum chamber device, and portraits of figures Jefferson admired. The room is underneath the dome, and looks out onto the lawn of the home.

The dining room at Monticello is painted a bold yellow and, like Jefferson’s bedroom, has a skylight. Adjoining it is a small sunroom. The room is directly above the wine cellar, and dumbwaiters inside the fireplace can transport bottles between the floors.

The guest bedroom on the main floor of Monticello is called the Madison Room. When visiting from their home Montpelier, James and Dolley Madison would often use this room. The wallpaper is a reproduction of the original pattern chosen by Jefferson.

To get between the upper three floors of Monticello, these narrow, steep stairs are used. There are two identical sets of stairs in the home.

This room Monticello’s second floor was used by Anne Scott Jefferson Marks, Jefferson’s youngest sister. She lived in the home after her husband’s death in 1811. She was often ill, and many of Jefferson’s grandchildren found her overbearing.

This room at Monticello belonged to Martha Jefferson Randolph, Thomas Jefferson’s daughter. This room was decorated by her and is the only room without an alcove bed or a bed jutting out into the middle of the room.

While the original wallpaper is long-gone, traces of it can be seen in a patch above the fireplace.

This room at Monticello served as the nursery for the children of Martha Jefferson Randolph. The room is adjacent to Martha’s bedroom. The nursemaids were all enslaved, including members of the Hemmings family.

This Monticello room is located directly above Jefferson’s office and next to the nursery. It was home to Jefferson’s older granddaughters.

Jefferson’s grandsons used this room on the third floor. It has two alcove beds and is filled with toys, games, maps, and even a surveyors chain.

Thomas Jefferson’s daughter, Martha, had a difficult relationship with her husband Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. A governor of Virginia, this small room on Monticello’s third floor was his bedroom.

The dome room at Monticello is one of the home’s most impressive spaces, though it is entirely decorative. It was occasionally used for storage or as a guest bedroom but was meant mostly for showing to visitors.

The glass in the oculus gave Jefferson trouble. He hoped it could be one piece of glass, but every time he ordered a custom-made piece from Europe it shattered. He eventually settled for two pieces of glass, which survived the voyage.

This small room is the South Pavilion of Monticello. It was the first piece of the house built, and construction began on it in 1770. Inside is an exhibit focusing on Thomas Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson.

At the end of the north wing of Monticello is a pavilion used by as study by Jefferson’s son-in-law. It was one of the last parts of the house completed. The pavilion was closed when I visited, so I was not able to get interior photos.

Slavery played a very big role in Thomas Jefferson’s life at Monticello. Enslaved laborers worked across the plantation and in the wings of the house, recessed into a hill and out of view from the main home. Many of their individual stories are told in exhibits in these parts of the home, including this exhibit about descendants of those enslaved at Monticello.

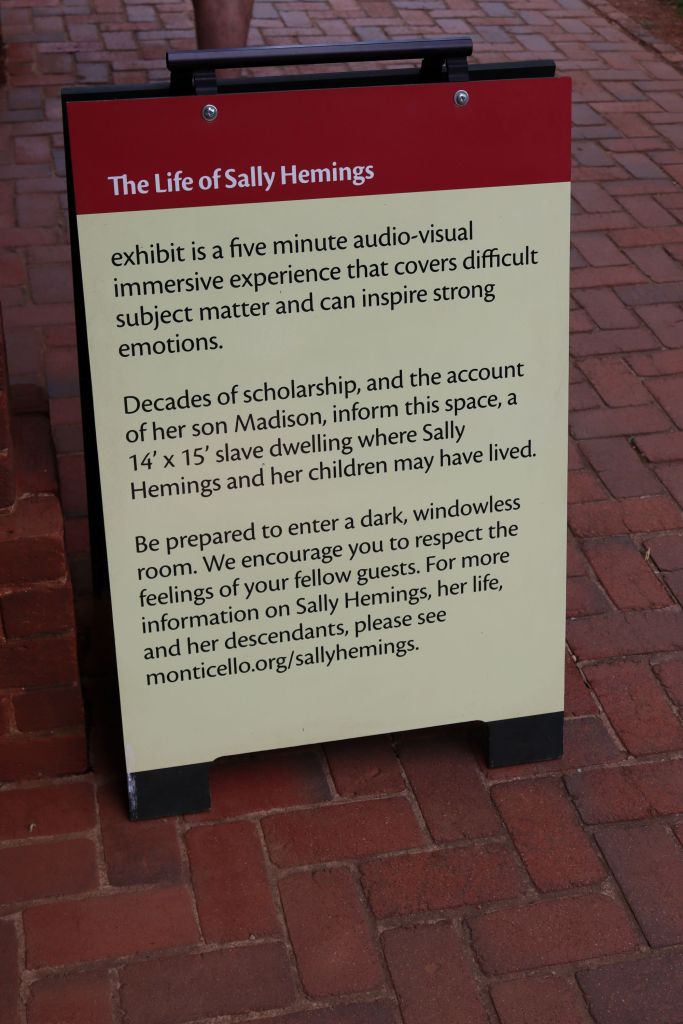

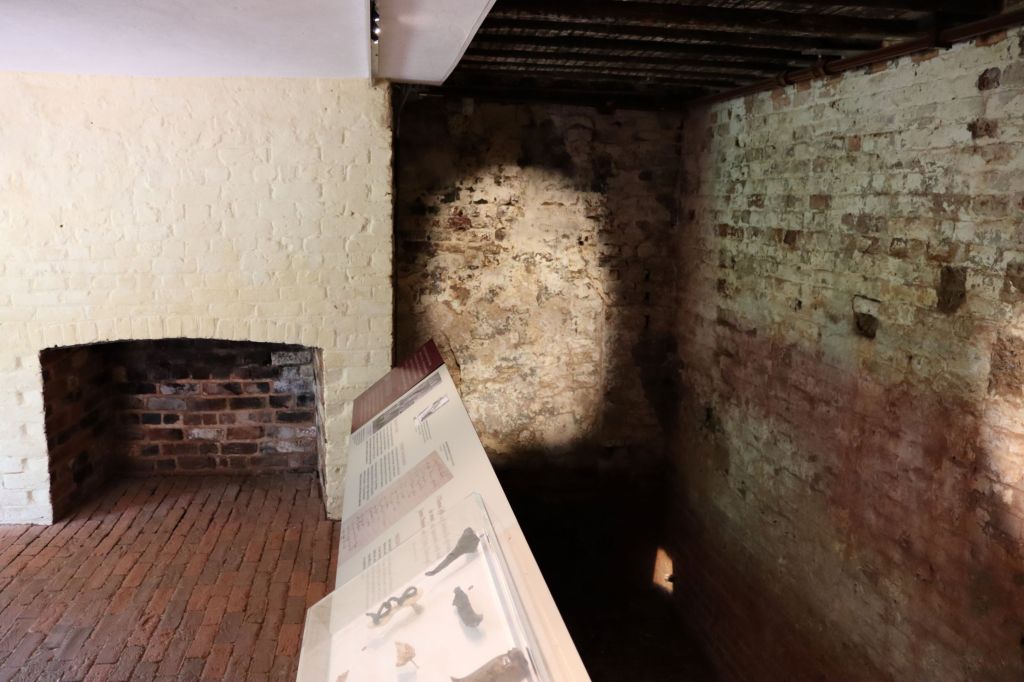

Aside from Thomas Jefferson himself, Sally Hemmings may now be the best-known resident of Monticello. She was born enslaved in 1773 and had six children with Jefferson. Her story is shared at the house through several exhibit panels and a very well-done and thoughtful short film inside the south wing.

This kitchen at Monticello is underneath the South Pavilion and was used by James Hemmings. The brother of Sally Hemmings, James Hemmings learned about French cooking in Paris. He was freed by Jefferson in 1796 but tragically committed suicide just five years later.

The floor of this room was originally much lower and was raised in 1808. The remains of the original floor have been excavated and seen inside today.

The south wing of Monticello is home to several rooms used to feed the main house, including a dairy, smokehouse, and large kitchen. Also here is a bedroom used by one of Monticello’s enslaved cooks, Edith Fossett, and her husband Joseph.

Directly beneath the dining room in the main house at

Monticello is a wine cellar, while a beer cellar is nearby. When the Marquis de

Lafayette visited in 1824, the entire wine cellar was emptied.

The north wing of Monticello was home to carriages and an icehouse. The icehouse was built in 1802 and is sixteen feet deep. Ice was collected in the winter, and it usually lasted until summer.

After leaving the presidency, Jefferson helped to establish the University of Virginia, and worked on the design for the campus. The centerpiece was the Rotunda, built as the library. To this day, the Rotunda can be seen through the trees at Monticello, though it can be a bit hard to spot.

To the south of Monticello was a row of structures called Mulberry Row. Found here were houses for those enslaved at the plantation and several workshops. Originally, a tall fence ran behind it. Only a small section has been rebuilt today.

In order to illustrate what life was like for those enslaved at Monticello, a replica slave cabin has been built. There were many houses like this all up and down Mulberry Row.

Monticello’s Mulberry Row has several structures used by enslaved workers, some original and some reconstructions. These include a blacksmith’s forge, a textile building, and a chimney surviving from a wood joiner’s shop.

To the south of Monticello is a vegetable garden. At one point, before the garden was restored, this was Monticello’s parking lot. Here Jefferson had a small structure for reading and writing, offering majestic views of the surrounding mountains.

After Jefferson’s family sold the house and before it was purchased by the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation in 1923, Monticello was owned by the Levy family. The first Levy owner was Uriah Phillips Levy, the first Jewish American commodore of the US Navy. Commodore Levy’s mother is buried on the property.

More information about the fascinating story of the Levys can be found in “Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built” by Marc Leepson.

Walking down the hill from Monticello brings you to the Jefferson family graveyard. Here, the third president rests underneath a marker erected in the 1880s. Unlike the rest of Monticello, this portion of the property is still owned by Jefferson’s family. It continues to be used for burials to this day.

After visiting Monticello, I attended a course at Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. I plan to share photos from the campus soon. In addition, I will soon be sharing photos from my visit to Jefferson’s other house, Poplar Forest. Stay tuned!

Interested in subscribing to my blog? Type your email below to be notified about new posts.

3 thoughts on “Trip Photos – Monticello”

Comments are closed.