The article below was written for Around Kennesaw magazine, but I ultimately decided to go in a different direction for that month’s article. It tells the story of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner’s connections to Kennesaw and the nearby forgotten African American summer resort.

If you are interested in more information about this story, feel free to contact me here.

NOTE: In April 2025, I presented a more complete version of the Wigwam’s story at the Symposium for History Undergraduate Research at Mississippi State University. That paper can be found here: https://ajbramlett.com/2025/04/26/symposium-for-history-undergraduate-research/

Henry McNeal Turner was born in South Carolina in 1834. Neither of his parents was enslaved, making Turner himself free as well. When he became a janitor at a law firm at the age of fifteen, Turner received his first true education. Using this knowledge, he was able to become a Methodist minister before he turned twenty. Turner preached around the South and joined the African Methodist Episcopalian church. During the Civil War, he lived in Washington D.C. Turner was commissioned as the Army’s first African American chaplain in 1863, and after the war, returned to Georgia as part of Reconstruction. Turner founded hundreds of churches in our state, including Mount Zion AME in what is now Kennesaw.

Politically, Turner helped established the Georgia Republican Party and was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1868. He and the other African American legislators elected that year were expelled by the legislature but were reinstated in 1870. Turner became a bishop of the AME church in 1880 but proved controversial, as he ordained a woman as a deacon and supported emigration to Africa. Regardless, he remained one of the most influential African Americans in the state. Henry McNeal Turner passed away in 1915 and was laid to rest in Atlanta’s South View Cemetery.

Bishop Turner has several connections to our area. As already mentioned, he founded Mount Zion AME, located near Shiloh Road. A small marker outside the old church building mentions his connection to the congregation. Additionally, research by Dr. Tom Scott of Kennesaw State University unveiled that Turner owned land off of Cherokee Street.

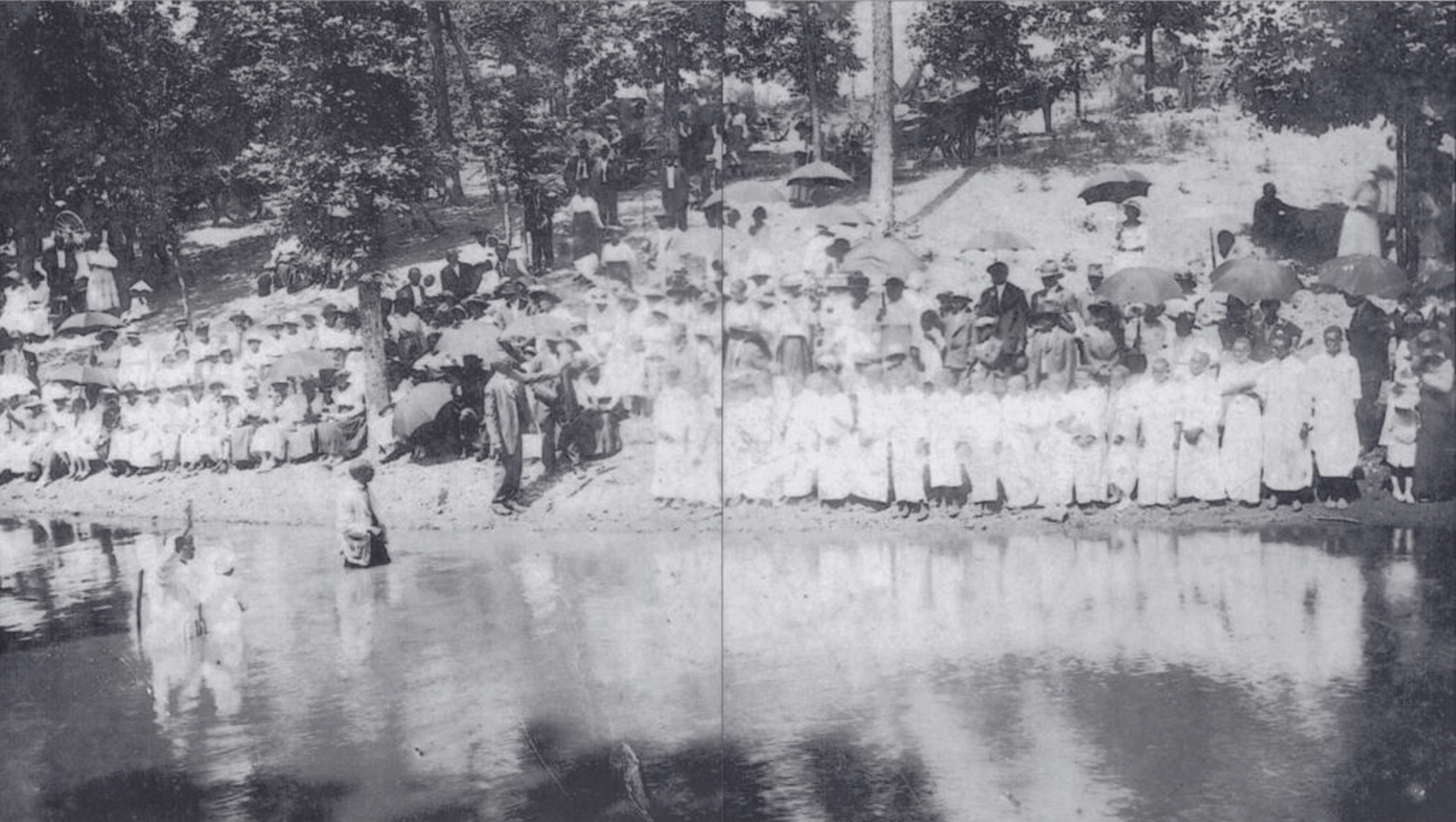

Turner’s son-in-law, Atlanta businessman Cornelius King, owned forty-seven acres of land near what is now Cobb County International Airport (Note: See addendum at bottom of page). On the land, he had a summer home, an artificial lake, and tennis courts. As more and more friends of the King Family came to visit, Cornelius realized it could be a profitable venture. He turned this land into a summer resort called King’s Wigwam. King’s family had Cherokee and Sioux members, which may be the origin of the resort’s name. The earliest evidence of its existence is a 1918 baptism photo from the resort, though the resort very likely predates the photo. There are stories of a David T. Howard having a stake in the resort, but I have not yet found evidence for this. Interestingly, Howard was later the undertaker when King passed away in 1934.

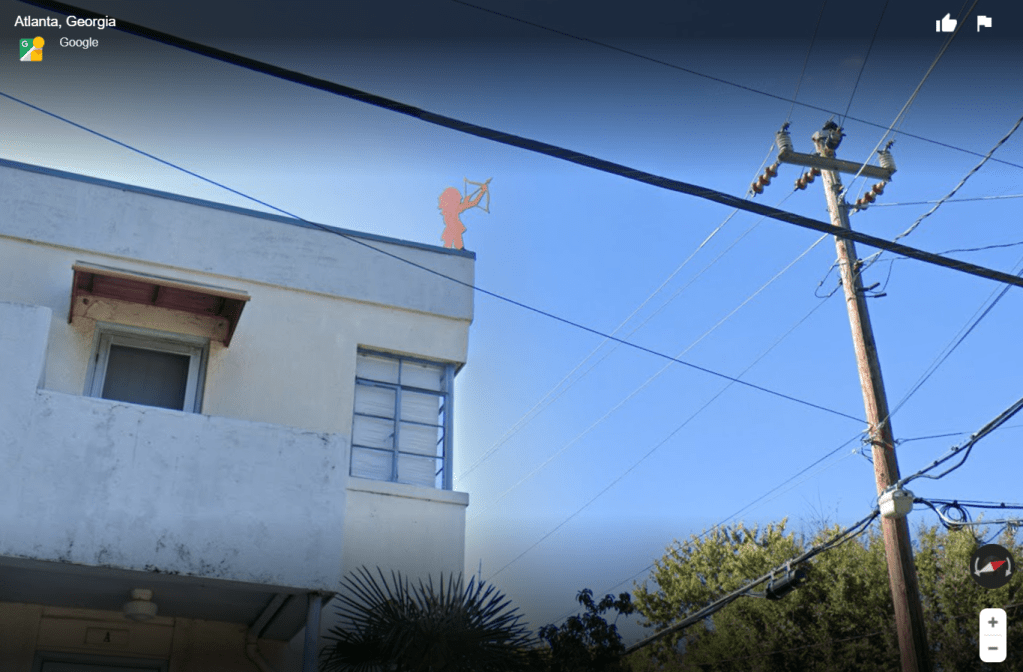

At King’s Wigwam was a large steel cut-out of a Native American with a drawn bow, which had previously sat on top of King’s house on Auburn Avenue. The resort’s lake was used by area churches for baptisms. Also at the resort were cabins available to rent and a dance pavilion. One account of the resort, from Stephen Birmingham’s 1977 book Certain People: America’s Black Elite, mentions that the people of Kennesaw were welcoming to the travelers and that the Kings frequented area stores.

In late July 1919, Bertram Hamilton of Atlanta was visiting King’s daughter. Hamilton’s father was a well-respected Atlanta contractor, and Bertram’s sister-in-law, Grace Towns Hamilton, was the first African American woman elected to the state legislature. While Bertram was visiting the Wigwam, he was accused of assulting a white woman in Cherokee County. To prevent his lynching, with help from the sheriff the Kings hid him in the trunk of a car and took him to Atlanta. The Kings were never able to return to the resort and soon sold it at a loss. Cornelius King’s daughter, Nina Miller, had suspicions that the allegations against Bertram “was part of a plot” by area residents to get the land. In 1977, it was noted that “she [hoped] this isn’t true, but it might have been.”

In 1941, the steel cut-out Native American was placed atop an Atlanta apartment complex called the “Wigwam Building.” The King Family had built the structure. It still stands proudly over Auburn Avenue and is the only remnant of the once-prosperous Kennesaw area resort.

Addendum: December 16, 2024

At the time I wrote the above article, I had not visited the Cobb County Deed Room to confirm the location of the property. The reference to the Cobb County International Airport is based on information shared by Davis McCollum, former administrator of the Old Marietta (O.M.) Facebook page.

On December 16, 2024, I was able to find information about Cornelius King in the county’s property records. In 1911, he purchased property in District 20, on land lots 129 and 100, from Henry M. Turner. There was a property trade in 1912, leaving King with around 45 acres of land. On August 31, 1920, about a year after the attempted lynching, the property was sold to J. D. Hilderbrand for $3500. This is the only property I can find that was owned by Cornelius King in Cobb County, and based on the sale date I believe it is the Wigwam.

By consulting the property description in the deed record, and a map of land lots, I was able to confirm the Wigwam’s location. It was between Cherokee Street and the railroad tracks, close to Ben King Road and the Tara subdivision. This is the same land purchased by Turner in 1889. I could not help but note the irony in the fact that this land is now home to Scarlett Lane and Rhett Drive, along with streets named Tara, Twelve Oaks, Melanie, and Ashley.